Waiting to enter, the history began to unfold. As I glanced past the modern idle ambulances, the beauty of the porticoed walkways conveyed its antiquity. This entrance is a mere 400 years old, a recent upgrade to the 1286 facility.

Once inside, through the automatic doorways, the lobby was not unlike many others. Couches framed the main hallway, busied with the crossing of staff in scrubs, wheelchairs whizzing by and staff using their badges to disappear behind doors as quickly as they appeared. Some were walking with heads high on their way out; visitors were walking in with nervous and blank looks with slumping shoulders. If it wasn’t for the Italian speech floating around, I could have been at my home hospital.

I am about to walk through Santa Maria Nuova, in the heart of Florence.

The tour will travel back in time 731 years, transporting me from hospice to hospital, from physic to internist, garden pharmacy to modern therapeutics, barber surgeon to cardiovascular surgeon, nuns to nurses. Physicians walked these halls arguing Galen and Mondino. Then in the 1500s, they circulated through the cloister arguing Harvey’s views of blood flow. Harvey set Galen on his head, as did Vesalius before him, both having trained in Padua. Santa Maria Nuova has continuously cared for patients for over 700 years.

My visit there this past summer was to uncover some of its secrets and soak in a center that cared for patients dying of the Black Plague and still lives to talk about it. But someone else lures me into the hospital’s story. The medical lore that runs through the hospital echoes loudly as I walk through.

It can be heard more intently than any other of the historical features.

“Da Vinci was here.”

There’s no banner with that announcement, and I wasn’t going to find that scratched into a bathroom stall or hospital bed. Few walking through today probably recall one of Santa Maria Nuova’s most famous interns.

Yet, I can feel his presence.

He was in the basement, working by candlelight. Two of his most famous dissections occurring steps away. The locations where he dissected are still down there but are not part of this tour.

It’s one thing to read about his work; it’s another to be occupying a space he once walked through. Da Vinci did dissections before many physicians were even allowed to, or even considered that it was a necessary part of education. The pope allowed for dissections by papal decree in 1482.

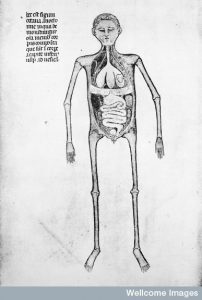

Compare the drawings of an earlier anatomist Mondino to an anatomical da Vinci drawing.

Anatomies de Mondino dei luzzi Guido de Vigevano

Charles Adolph Ernest Wickersheimer

Published: 1926

Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

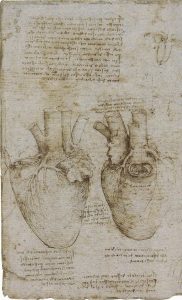

Leonardo da Vinci’s drawings of the heart, c.1511-13 Photo: The Royal Collection Trust © 2012 Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II

The first dissection done at Santa Maria Nuova, by da Vinci was on Il Vecchio, the old man. The elderly patient passed away in a “dolce morte,” or sweet death, simply of old age. The curious da Vinci, wanting to find out the cause, immediately searched for an answer in the basement of Santa Maria Nuova in 1502. He saw a heart with vessels looking like squiggly lines, with thickened walls. He also dissected an infant around the same time and noted the heart vessels to be straight lines, with clean tunnels. His comparative notes and description are the earliest depiction of arteriosclerosis. Nothing like this is described for another 400 years.

Da Vinci’s incredible drawings were lost to science for hundreds of years, only recovered in the late 1800s. The master was seeing for himself, but also seeing only for himself. He talked about publishing his work but also talked about how his drawings were for his own edification. The dissections and drawings were to further his artwork, to search for why, and to see for himself. He also knew a good drawing could explain more than pages of text.

The self-educated polymath, with an unending thirst for knowledge, and hence wisdom, teaches and inspires endlessly. The importance of observation, seeing for yourself,

These lessons are relearned every day. The exam finding missed because of a cursory observation, the hidden bit of history elicited with a good history. The picture or drawing shown to a patient for education, better than muddling through that description of the gallbladder, or a cardiac cath. We are constantly searching for truth, uncovering the hidden stories, and trying to explain the complicated in a simple way. We will never come close to the mind of da Vinci, but we can constantly learn from his genius.

Next time, perhaps I can get into the basement where he actually did the dissection. But his presence and messaging were felt simply walking the halls of Santa Maria Nuova. A hospital that has been continuously operating since the time of Kublai Khan, since Dante, and continues to serve the residents of Florence.

To read more about da Vinci, check out one of the following, or one of the hundreds of books about this genius:

Buy this app from the Royal Collection Trust, which includes all of his anatomical drawings in digital format

Sherwin Nuland’s short biography

Kenneth Clark’s classic book

Leonard Shlain’s posthumous readLet me know about some of your favorite da Vinci books.

Leave A Comment