Working as a hospitalist since our society’s founding, I have reaped insights and a dose of confidence those starting in our specialty lack. I am not speaking just of clinical understanding.

Hospital-based practitioners collaborate with colleagues from many specialties, and like us, each has its own identity. Surgery sees the world through their lens, as do we.

Over time, through the dances we do, we come to expect a predictable dynamic when we interact. Presumably, the dynamic produces a mature partnership built on respect. One discipline welcomes the efforts of another, and in turn, all parties feel appreciated. That’s a good thing.

Conversely, there are times one feels a lack of esteem, or worse, abuse. As the latter view relates to hospital medicine, I can often decode a request to comanage versus play domestic, or babysit versus oversee. And I should add, if you receive a voicemail in lieu of a live call to make those requests, you can bet someone knows something you don’t.

Just like other specialties, hospitalists aspire to have a professional identity—no different from intensivists, electrophysiologists, and physiatrists.

Perhaps due to immaturity as a field or use of a playbook whose rules still need ripening, newbies and itinerant worker bees sometimes may go along to get along–for myriad reasons. Whether compelled by others or out of dread, saying yes becomes the norm. Without grounding and role models to observe, these default actions impede our growth by self-perpetuating a semi house doc label. From listening to conversations, talking to colleagues, and reading posting boards, I sense more of this occurs than we like to admit.

From my vantage point, with a decades plus experience in my pocket, fuzzy boundaries have sharpened. I have a greater sense of propriety. Saying no to the ICU “dump” or vascular transfer on account of, “no further surgical indication present” does not feel out of sorts. Further, not acceding into a discharge master or emcee role for conditions I have no knowledge of, and whose interventions I play no part, also does not feel like an abrogation of my duties.

The referring physician will utter, “What does a hospitalist do anyway—you don’t want my patient?” The subtext goes beyond a request rebuffed: cloaked in the appeal rests an uneasy mix of time, money, ego, and aggravation. We relent, but the acquiescence comes with a price. Our professional identity, as I mentioned above, and esteem suffer.

Some of you practice in community hospitals with associates you trust. Personal relationships make uncomfortable conversations unnecessary.

However, these sociable settings alleviate the problems tertiary and quaternary teaching hospitals with trainees have entrenched within their walls—where over half our membership practice. Something about the formidable culture in large institutions perhaps, but specialists perceive us as their subordinates in the practice hierarchy.

I don’t have evidence to confirm my view. But again, the trend I glean from colleagues, along with my own experience, seems to be more signal than noise.

Therefore, I attempted to strengthen my suspicions with data.

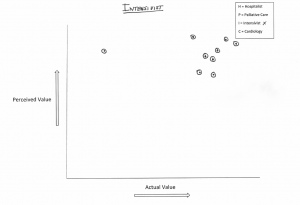

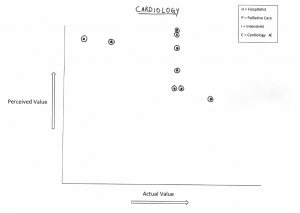

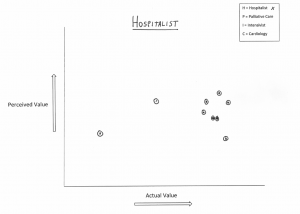

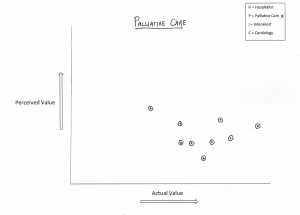

To that end, I engaged my team in a short non-scientific exercise. I asked them to plot their impression of how the world at large, defined broadly, views the worth of various specialties versus how they see them. They assessed the following four disciplines: intensivists, cardiologists, palliative care docs and hospitalists.

(I should add, my group has an even mix of experience, ethnicities, males and females, and years in practice. In addition, they hail from various sites of training.)

I plotted their answers, mine included, into four graphs below—cards and ICU on top, PC and HM on the bottom (click to enlarge):

Are you surprised where each discipline fell out? Do you notice a pattern? If you don’t, let me make it easy: if we were on the Serengeti, we would not be the lions.

Now I could speculate about how any specialist might rate themselves and the biases each would bring to the table. I could also speculate proceduralists and physicians engaged in high tech care have deeply embedded cultural advantages in U.S. medicine—and no matter how we spin the story, docs without toys will always drop to the lower rungs of the ladder.

However, I think our station has much to do with our need to mature as a field, and how the public (and HM) views a young, unassimilated specialty.

Many of us still lack confidence. We bristle when we watch folks react to our telling them of our vague job description and name (“you’re a what? A hospice-a-list?”). Our families still tell neighbors we practice (just) internal medicine. Our media stories, while somewhat favorable, still have a sterile, matter of fact character about them, with the usual primary care disclaimers at the close. The ones dispelling any notion we might have built a better mousetrap or we enhance, rather than detract system value.

And how do I connect a practice of saying “no” to our self-perceived worth as a specialty? It’s hard to wrap up in a short post, but let me try with a metaphor.

Like a parent to child, or mentor to mentee, regardless of how much time passes or knowledge the lesser acquires, an asymmetry exists. One party elevates over the other, and nothing either does will alter the equilibrium.

Friends and acquaintances are different, however. A certain comity exists between them and each side understands the other. It is a partnership of equals.

As hospitalists, many of us operate with our mindsets in universe one, whereas many of our colleagues with established relationships are in world two. As much as SHM has grown, we still need a dash more gravitas and time to reflect before we cross over.

Saying “no” represents more than an uncomfortable phone call or misdirected request. It’s also not about burning bridges or conveying ill will. Saying no sometimes means telling the person on the other end of the line, I am not your child, but your friend. And that’s okay. We all must grow up.

Brad,

Thanks for your thought provoking post on a topic which I find myself pondering daily. I think these issues are central to our well being as a specialty as well as our individual satisfaction with the work that we do. Allow me to expand on some of your themes.

I understand the value to the hospital and our colleagues on our respective medical staffs, especially when it comes to the support we provide to a surgeon whose patient has unstable medical problems. Our collaboration allows us to care for that patient to the mutual satisfaction of the patient who prefers our institution and to the hospital’s financial goals. Moreover, the patient receives better care.

There is a danger, as you point out, that we are left “holding the bag” for a specialist who doesn’t want to be burdened by busy work or who feels uncomfortable using a new EMR. I see this dynamic on a daily basis. I will never decline a request to bring my expertise to the bedside when my input is valuable. Just don’t expect me to function as your housestaff. I have the gray hair and glasses that make these “negotiations” more equitable but I see my younger partners caught in these situations more frequently.

My concerns are personal and professional. On a personal level, being responsible for a patient for whom my skills as an internist are underutilized is not satisfying. As I like to say, if you treat a hospitalist like a resident, they will treat their job like a residency and move on after a few years. From a professional standpoint, the lack of an even playing field degrades our identity and value as a specialty and we all suffer.

Thank you for saying what needs to be said and fostering an environment that helps us all gain the professional status we deserve.

Bob

——————————————-

Robert Lineberger MD, FHM

Hospitalist

Duke Regional Hospital

Chapel Hill NC

——————————————-