I did not think I would ever quote Donald Rumsfeld in one of my blog posts, but some of the missed opportunities as well as the media and public panic surrounding the Ebola epidemic in West Africa have brought this quote to the forefront of my mind this past week.

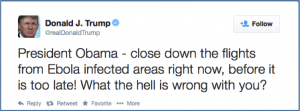

First, let me share my personal view of the Ebola crisis in West Africa. It is a tragedy in all senses of the word for Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone. As a wealthy country and as global citizens we have a moral obligation to assist in the control of this outbreak and to help these countries build/rebuild their health and economic infrastructure after the devastation wrought by this disease. If the moral argument does not do it for you, remember that we have self-interest here, too. We benefit domestically from increased control of the disease in Africa and fewer cases found and treated in the U.S. I personally find that justification distasteful, and I strongly disagree with the sentiment voiced by another Donald (Trump) that anyone who goes to help out should “suffer the consequences” or that “all flights from Ebola Countries should be shut down” as seen here:

And I guess that is part of our problem. We give airtime to sensationalism. Loudmouths like Trump and others who have no apparent background in the science or epidemiology of Ebola. We live in fear of Ebola as an “unknown unknown.” We don’t know what we don’t know about it, but any disease that is fifty percent fatal sure sounds scary. I think that people hear “Ebola” and have a similar visceral reaction to “anthrax,” or “bioterrorism,” or “SARS.”

Our own ignorance and insecurity leave us vulnerable to overreacting to sensationalism and fear-mongering which are so prevalent in our internet-based culture. Headlines like the UN warning of ‘nightmare scenario’ where Ebola ‘could become airborne’ (when in actuality the article quotes the source as saying that this is an extremely unlikely event that would be a nightmare). Panic can lead to the emptying of a police station, or parents keeping their children home from school. At this point, it seems that a patient with Ebola infects about as many patients as one with Hepatitis C. This does not mean that it is similar to Hep C, but it is only transmissible by someone who is showing symptoms (no symptoms = no transmission).

Fear and ignorance make it difficult for us to understand the true tragedy of the disease. Right now, there are thousands of people dying of this disease in West Africa. The reason they are dying is that there were not enough beds or providers to care for ill patients BEFORE the outbreak started, and now that inadequate infrastructure has been overwhelmed. There are not enough beds, gloves, clean water, nor basic sanitation. Beyond Ebola, thousands more people are dying from lack of treatment of malaria, lack of prenatal care, inability to access other basic medical care, and malnutrition.

Back at home fear and ignorance make it difficult to sort through the myriad of news on the TV, radio, newspaper and internet to try to get accurate information. Here are my answers to a few questions I have heard bandied about:

Q: Is Ebola transmissible by the airborne method or not?

A: No – there is no evidence of this, and it unlikely to mutate to become airborne

Q: Do we need to care for patients in a biosafety level four type of center?

A. No, standard contact and droplet precautions are all that is necessary (NOTE – since my original post, the guidelines have changed. Click here for the latest changes as of 10/16/14 – even with the changes, I think that we should still be able to safely care for Ebola-infected patients)

Q: What is the incubation period?

A; 21 days at most, but most people develop symptoms earlier (by 8-10 days).

I have my own set of worries about our domestic response to Ebola. I worry that patients feared to be infectious will be unable to get care, leading to possible spread of disease. I worry we will miss other diseases – malaria and typhoid fever are far more likely in a returning West African patient than Ebola. I worry that our immigrant and refugee communities will be stigmatized for a misperceived role in spread of disease. And I worry that when this crisis is over, we will continue to poorly fund our scientific institutions that lead to a better understanding of illnesses like Ebola.

We physicians have responsibility and culpability here as well. As a hospitalist at a large academic urban hospital, I am one of the first people (after my ER colleagues) to see someone who is sick enough to need to be admitted to the hospital. I have a responsibility to my patients to ask appropriate questions to get to a diagnosis as quickly and efficiently as possible. As physicians, we need to be able to recognize and manage what is most likely, what could kill the patient, and what could have an impact on public health, and then we need to prioritize our work-up and interventions.

We live in an increasingly mobile and interconnected world – one in which we can travel between any two points in the world within the incubation period for any infectious disease. I assume that we will continue to see more cases of Ebola that are diagnosed here in the U.S., so we best be prepared to manage both the patients and the fear/ignorance (both our own and that of the broader public). Remember that two of the most important questions to ask someone as part of a history and physical are “Where were you born?” and “Where have you traveled?”

In medicine, it is not the “known unknowns” that I worry about; these are manageable. We recognize a gap in our knowledge, and we order tests or call in help by getting consultants involved. It is the “unknown unknowns” that should be more scary for us. I would like to think this was the case in Dallas that led the patient to be sent home from the ER on September 26th despite showing symptoms of Ebola and telling staff there that he had returned from Liberia. I do not think that patients expect us to know everything, but I do think they expect us to know our limitations, recognize red flags, and know when to ask for help.

So, for all my colleagues who work in health care, I have a few requests:

1.) Remember the social contract that we agreed to as doctors, nurses, and other providers: We cannot abandon patients who are suffering in the midst of this crisis. Some of the comments out there come uncomfortably close to the stigma and fear around the HIV epidemic in the 1980s and 1990s, with health care providers refusing to care for patients with AIDS.

2.) Be a voice of reason amidst hyperbole and sensationalism. Do not underestimate or overestimate the seriousness of this epidemic, both in Africa and here in the U.S. Consider calling your congresspeople to encourage decent funding for scientific research. We are seriously underfunding all areas of research across all disciplines. In medicine, this includes infectious diseases like Ebola, but also noninfectious ones like ALS.

3.) Be aware of your own limitations and gaps in knowledge. Take steps to address these gaps, whether it is more learning, or a consult to a colleague with experience in the area.

4.) It is okay if you do not know everything about Ebola, and it is even okay to be scared of it. But learn about it, learn how to prevent spread, and find out what your hospital would do if you have a patient with it. Running out the door is not a morally viable option, and remember that it is FAR more likely that the patient has something else.

Personally, I think the best information about the Ebola epidemic has come from our own Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and I would suggest people start there for information.

UPDATE: To follow up on Dr. Hendel-Paterson’s recommendation about the CDC, the CDC is hosting a conference call TODAY (Tuesday, October 14) called “Preparing for Ebola: What U.S. Hospitals Can Learn From Emory Healthcare and Nebraska Medical Center.”

Here are the details:

http://emergency.cdc.gov/coca/calls/2014/callinfo_101414.asp

Very well said. Thank you!

Well said Brett

Well written, thank you for addressing this important issue!

Thank goodness there is still a voice of reason in this country.

If this nation is to fall, it would most likely be from complaceny and self-righteousness, also known as political correctness. Despite what you have said about unknown unknowns, I don’t think you have given due respect for this deadly disease, which is clearly highly infectious, airborne or not. The CDC which you have placed much faith in is now proved to be capabe of jaw-dropping blunders such as slow response to Duncan case and allowing air travel of a health worker who took care of Duncan , and its lax guidelines are now under further scrutiny. Trump’s proposal, cruel as it sounds, is cautious and justified. This is a disease which has been pojected to have over 1M patients by December and it is hard to imagine how we are not going to have another Duncan at our gate soon. The enhanced airport screening has proven to be a joke with the long latency of the disease, and the motive for people to lie to get out of the country. Duncan did manage to go through, didn’t he? The United States health system is clearly not ready for this with 2 health workers contracting the disease while many potential contacts are not accounted for.

Thanks Maggie for your comment. I hope that this post didn’t come across as self-righteous – that was certainly not my intent. And we need to hold leaders and systems accountable for missteps (like seeing why the latest person was allowed to fly with an elevated temperature). But I disagree that the CDC has had “jaw-dropping” blunders.

I am very concerned about this deadly disease that is killing so many thousands of people. And I suspect we will see more cases in the U.S., too (possibly more cases in health care workers who cared for Mr. Duncan that have not appeared yet). We need to learn as much as we can to make sure we have adequate prevention in place to prevent an epidemic in the U.S.

But I disagree that closing our borders is the right approach. True, it is cautious, but I do not think it is justified or would be effective. In our highly mobile world, there are plenty of ways to get to the U.S. other than directly from West Africa. It is true that there may be incentive to lie or minimize symptoms to get out of Liberia, Sierra Leone, or Guinea. And you are also correct that the incubation period means that people can be infected but don’t show symptoms. Screening for fever in people who flew from West Africa is a start, but it’s not perfect. I don’t want us to have a false sense of security that banning flights will keep us safe. We need to have a high level of vigilance so we don’t miss cases, and all of us who work in health care need to make sure that our systems have plans in place to deal with a possibly infected patient. We also need to make sure that all of our health care providers have a clear idea about what is needed to keep them and our patients safe, while we care for people who are ill. As you point out, we will likely have another patient like Mr. Duncan soon.

I am also concerned about the conspiracy theories I have seen floating around, some suggesting that the government is trying to control us or deliberately ignoring the threat of Ebola.

We need to stay levelheaded and calm about our approach. I’m sure there will be changes in infection control protocols, and maybe even changes with where infected patients are cared for (like transferring to the CDC in Atlanta).

I do have faith in our CDC. I have worked with a number of the people who work there. The folks I have met are professional, intelligent, and they do good planning almost all the time, working within the constraints of their mandate and budget. They are also human, and gathering information can take time.

I advocate for a multi-tiered approach

1.) Screen people in airports for symptoms (you can’t transmit the disease if you are not symptommatic)

2.) Every hospital and clinic should have protocols in place to deal with Ebola or any other potentially alarming other diagnosis (what if another anthrax scare, or SARS, or pandemic influenza)

3.) Disseminate and continue to develop protocols for infection control to make sure health care workers are safe.

4.) Long-term, make sure that the CDC is adequately funded to do its job, and also improve our funding of basic science research, so we can have more researchers learning more about Ebola and other diseases early.

5.) Continue to educate colleagues in health care, and the public in general what constitutes a threat, and how to avoid getting an infection

6.) Remind people that there are other very preventable diseases that we should be vaccinated for (like influenza and measles)

Anyway – long response above, and thank you for raising these issues.

Thanks Brett for the detailed response. Agree with most of your points in your approach but think you are misguided on the flight ban. You might not realize there is NO direct flight to US from west Africa already and what needs to be done is to screen all passengers for their country of origins. The traffic is currently around 150/day which is not insignificant as new cases continue to accumulate and so does people at risk. Don’t get me wrong, I am all for providing these nations with all kinds of support from personnel to supply as they need, and have but the highest respect for colleagues fighting in the front with their own lives at risk. However, allowing the disease to spread to the US when it is clearly not ready is irresponsible and will prove disastrous. Regarding the alternative means of transportation to US you mentioned, to my knowledge there is none that would allow people at risk to arrive in US within the incubation period, and beyond that regular screening measures will work.

Thanks for your reply. We will have to agree to disagree on the travel ban. I think that the U.S. can be made ready with preparation, and the preparation is necessary. I don’t think that it will spread widely in the U.S., and it is already here. I am all for screening passengers for fever or other symptoms and quarantining/isolating as needed. But if they do not have symptoms, the risk of transmitting the disease is essentially nil. I do not think that adding a travel ban will keep us any safer and I think there are too many ways around it (depends on what other countries institute the travel ban, too, and also raises the question of what to do then with the people who are leaving West Africa). We already have people in the U.S. who have Ebola, and probably more who will be diagnosed with it over the next days and weeks. So we need to prepare country-wide to deal with the possibility of disease.

There may be some unknowns you didn’t consider.

A paper in PLoS Current Outbreaks (http://currents.plos.org/outbreaks/article/on-the-quarantine-period-for-ebola-virus/ ) suggests that the 21-day incubation period for Ebola may be a very soft number. The author suggests that 0.2% to 12% of patients may be contagious past the 21 days.

The CDC website (http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/transmission/index.html?s_cid=cs_3923) states that Ebola virus can be found in semen as log as 3 months after a patient recovers. Is semen the only fluid with this picture or are there others. Who knows.

Thanks for your comment, Skeptical Scalpel. The PLoS article came out after this post. I have to be honest – I don’t know how it affects the response/planning for Ebola. Perhaps a longer observation period is needed? The article seemed based mostly on mathmatical modeling,

It does look like semen seems to be the most pesistent fluid. Other bodily fluids have been tested and the infectivity drops off a lot sooner.

Here’s the link to one of the papers I found that talks about it:

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9988162

from the abstract, looks like the semen was PCR positive for Ebola virus, while other fluids weren’t, and

Oops – hit send too early. I meant – semen was PCR positive later in the convalescent period, while other fluids weren’t. In some other studies, there was a distinction drawn between PCR positivity and the presence of infective virus in the fluids. But the main up-shot is that abstinence from sexual intercourse is recommended for 3 months.

Brett,

Thanks for the insight. On the point of helping those in West Africa, where do you think funds are best directed? Which agencies are most efficient at getting the help to where it’s needed? For all the hype and sometimes outright fear-mongering going on, there seems to be very little emphasis on how people can help now. Thoughts?

My go-to would be Doctors Without Borders – my impression is that they are doing the best on the ground work getting care to those who need it.