The question of appropriate ward garb is a problem for the ages. Compared to photo stills and films from the 1960s, the doctors of today appear like vagabonds. No ties, no lab coats, and scrub tops have become the norm for a number (a majority ?) of hospital-based docs—and even more so on the surgical wards and in the ER.

Past studies have addressed patient preferences for provider dress, but none like a release from last week.

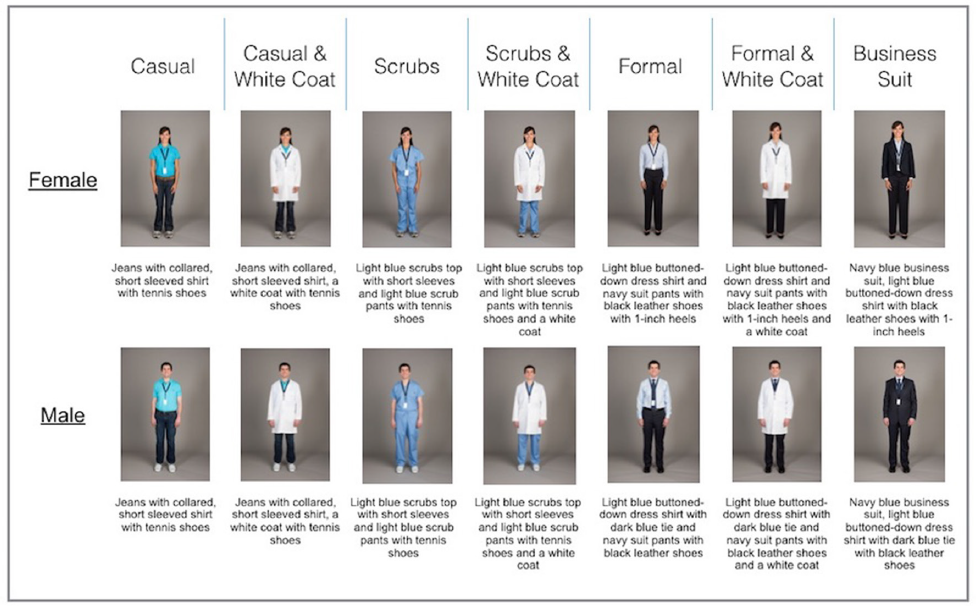

From the University of Michigan comes a physician attire survey of a convenience sample of 4,000 patients at 10 US academic medical centers. It included both inpatients and outpatients, and used the design of many previous studies, showing patients the same doctor dressed seven different ways. After viewing the photographs, the patients received surveys as to their preference of physician based on attire, as well as being asked to rate the physician in the areas of knowledge, trust, care, approachability, and comfort.

You can see the domains: casual, scrubs, and formal, each with and without a lab coat. The seventh category is business attire (future C-suite wannabees–you know who you are).

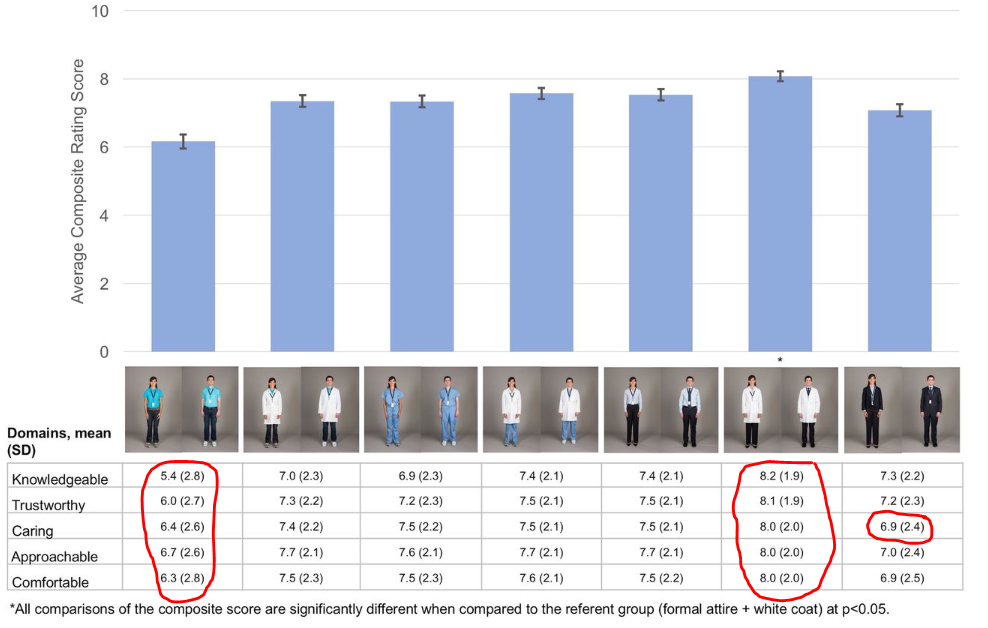

Here are the top line results:

Over half of the participants indicated that how a physician dresses was important to them, with over 1 in 3 stating that this influenced how happy they were with care received. Overall, respondents indicated that formal attire with white coats was the most preferred form of physician dress.

I found the discussion in the study worthwhile along with the strengths and weaknesses the author’s outline. They went to great lengths to design a non-biased questionnaire and used a consistent approach to shooting their photos. They also discuss lab coats, long sleeves, and hygiene.

But what to draw from the findings? Does patient satisfaction matter or just clinical outcomes? Is patient happiness a means to an end or end unto itself? Can I even get you exercised about a score of 6 versus 8 (a 25% difference)? For instance, imagine the worst dressed doc—say shorts and flip-flops. Is that a 5.8 or a 2.3? The anchor matters, and it helps to put the ratings in context.

During my training, I idolized my chair and program director. My PD is still a trusted friend to this day, and my chair was and is a nationally known figure. Yet on the weekends, they wore jeans and went casual. I still do that myself—partly as a Saturday and Sunday dress down and attire decompression, but also in part because of mental memory and emulation of my mentors. It was okay for them, so it is okay for me. Their patients adored them.

Despite the study, unless my overseers put hard rules into place, I likely will not become a haberdasher’s Saturday and Sunday dream cadet. However, if firm evidence proves we have a meaningful impact on patient experience based on our appearance, I will upgrade. Monday to Friday I am game on as the wards go and don the collar and neckwear. But for holidays, nights and weekends, yes, I am intrigued and will keep an open mind and wait for additional credible data.

Does our dress change how a patient feels and recovers? I am still hesitant on the latter, and on the former, as the patient gets to know you, how you physically represent yourself probably means less. But we have a lot to learn about patient experience and satisfaction. It’s a knowledge black hole now.

To move my thinking, the study I want requires a different approach. I need the same 4000+ patients but with actual docs dressing in the garb depicted in the photos (the number and distribution of providers to be determined). The study design would be a sound single-subject design and participants would wear casual clothes for six months and then switch to white coat formal for another half year. Patients would assess their docs not based on appearance but experience or satisfaction domains relevant to a set of tangible outcomes. Compare and contrast the same doc in the different duds and use them as their own controls. These outcomes should be marked enough for practitioners to take note of and force them to realize dressing down does them and their patients a disservice, i.e., trust, adherence to care plans, follow-up.

That kind of data would put my casual attire in the Goodwill pile and allow these guys to seek another round of funding. But call me an open-minded skeptic.

most patients see Doctors in an office based setting. This study was a waste of money and time. There will soon be a trend towards independent Physicians in a private practice setting. This is were it matters.

As a “Scrubs and white coat” Hospitalist, I am happy where I am. No C-suite business suits for me!!

I believe a meta-analysis of all surveys/studies done on this subject would be interesting. Virtually all prefer physicians in the business dress/white coat model. If this were an analysis about a medication or surgical intervention there would be no question which choice to make! This is taking skepticism to the extreme. Why, because physicians don’t want to wear ties or white coats! We look for medical reasons to support our desire; remember the question of the tie being a fomite for infectious diseases! Has there been a follow up to the British rule banning ties and long sleeve shirts in hospitals, I don’t recall seeing anything describing a significant reduction in hospital acquired infections. But this is not a classic medical issue, it is a customer service and confidence issue. Whether we agree or not, patient satisfaction is an issue. Patients (read customers in secular language) prefer a certain appearance. I also feel our patients are ill and scared, and they see there hospitalist/critical care/hospital based physician for on average less than 4 days. Anything that buoys confidence is worthwhile in my estimation. As far as I know, all hospitals have HVAC systems and usually they are cooler than we’d like. As a result, the tie and the coat should not be such a burden. Our group has a “tie/coat or scrubs/coat” policy, it works well and if it increases patient satisfaction scores, so much the better.

Interesting! In this paper, most patients were seen in the hospital, and I’m unsure why after this paper we wouldn’t want to present ourselves more professionally.

It would be interesting to also study differences in perceptions between clinicians of different ages and races. Surprised not to see more of a gender difference here.

It is key to note that patients (customers) do not get to choose their hospitalist. If they choose an outpatient primary care physician who dresses informally, so be it. However, in this setting perhaps we should be more mindful of customer preference as they are nearly powerless to make a switch if they do not feel comfortable with their hospitalist. This logic follows for ER docs as well…perhaps a similar study needs to be done to address patient preference in that setting, too. Agree that the study has weaknesses as discussed above, but I think it should at least promote discussion within groups.

“