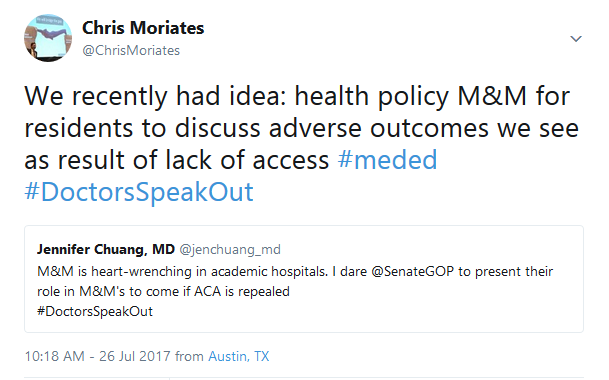

https://twitter.com/ChrisMoriates/status/890259986873450508

There are few experiences in my medical training that felt more intimidating, and ultimately more impactful, than our Mortality and Morbidity (M&M) conferences. The patients whose diagnoses I missed. The times I should have called my attending or pushed harder for the cardiologist to come in overnight. They stick with me and I believe ultimately have helped make me a better doctor. This is why I was intrigued by the idea of explicitly incorporating health policy issues into M&M.

Over the past few years, I increasingly have seen adverse events that result from issues related to health policy. Inability to access care for appropriate hospital follow-up. Failure to fill a critical prescription due to cost or gaps in coverage. A patient I admitted for “expedited work-up” for rectal bleeding after he told me he had been trying to get a recommended colonoscopy for many months but could not get it scheduled due to his lack of insurance. He had colon cancer that had spread.

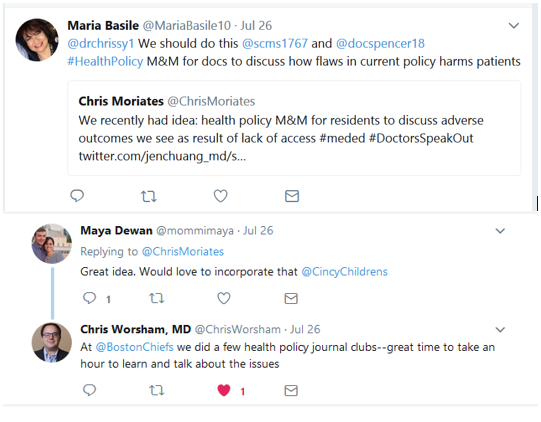

It seems the idea resonated with many hospitalists and medical educators on Twitter:

As Chris Worsham, previously a Chief Resident for Quality and Safety at the Boston VA, pointed out, reviewing health policy can be a great opportunity for trainees to learn about the issues. But it shouldn’t stop with trainees. All of us hospitalists should understand and discuss health policy issues that affect the health and care of our patients.

Let’s face it, though – there are just not enough hours in the day to keep up with clinical medicine and health policy. Thus, it is helpful to have members of the group who are particularly interested in the topic to prepare sessions to teach our colleagues. Lectures and journal clubs are probably fine. However, we all know that the educational sessions that truly capture our hearts and minds are case-based M&Ms. Pair the lesson and contextual data with a heart-gripping story and now you have a recipe for inspiring action.

I believe that if health policy issues were more explicitly integrated into M&Ms, then clinicians would be more inclined and prepared to effectively advocate for specific policy changes. Perhaps entire groups would be moved to engage in the political processes. Imagine a letter from a hospital medicine group to their local state representatives expressing why they believe patients need further regulatory protections from “surprise bills.” Ok, that one might not go over so well with hospital leadership or your friendly emergency department, but I can still dream…

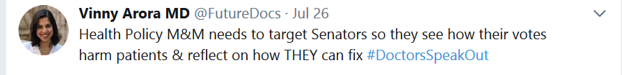

Speaking of dreams, Vinny Arora took the proposal one step further:

Maybe Vinny is right. I would like to cordially invite policymakers – statehouse legislators, my local members of US Congress – to join me in reviewing these M&M cases. To think about individual patients that are hurt by the system, based on political decisions, such as Texas’ choice to not expand Medicaid coverage. To see the real consequences and to strive together to avoid similar outcomes in the future. I know that many of these representatives don’t respond to constituent letters, visits, and town halls when aggrieved patients or families raise holy hell, so why would they possibly come to M&M?

This proposal is not meant to stick it to ‘em, but rather is based on a hope that they, like me, could gain insights without gratuitous blame or derision. The room should be sympathetic, but should also establish a clear sense of accountability. A professional, solemn, closed-door affair, rather than the hyper-politicized atmosphere of a town hall. No “gotcha” YouTube clips or soundbites.

The individual stories would be put into a larger context to help develop population-level policy decision-making. Just as policymakers could see legislation through the eyes of practitioners and their patients, this is where we as physicians could possibly learn from our legislators; we may recognize the potential trade-offs, downsides, and barriers to proposals that to us may have seemed like no-brainers.

There is plenty we could fix together when we recognize the true gaps that currently exist that harm our patients/constituents/neighbors. The first step will be meaningfully reflecting together on where we fall short – how we may have contributed to morbidity or mortality in those we are charged with helping.

Maybe it is time for a policymaker M&M. At the very least, we could consider incorporating this health policy content into our current M&M conferences to better inform our trainees and colleagues.

Acknowledgement: Chris Moriates would like to acknowledge Dr. Beth Miller, Internal Medicine Program Director at Dell Medical School, for first mentioning the idea of a “health policy M&M” to him.

Leave A Comment