The policy known as Meaningful Use was designed to ensure that clinicians and hospitals actually used the computers they bought with the help of government subsidies. In the last few months, though, it has become clear that the policy is failing. Moreover, the federal office that administers it is losing leaders faster than American Idol is losing viewers.

Because I believe that Meaningful Use is now doing more harm than good, I see these events as positive developments. To understand why, we need to review the history of federal health IT policy, including the historical accident that gave birth to Meaningful Use.

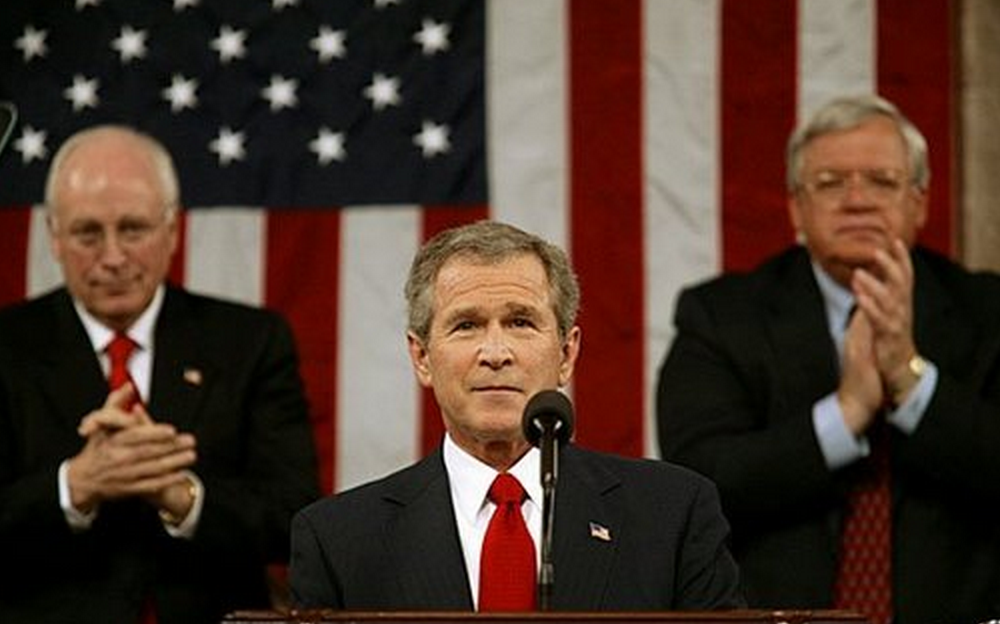

I date the start of the modern era of health IT to January 20, 2004 when, in his State of the Union address, President George W. Bush made it a national goal to wire the U.S. healthcare system. A few months later, he created the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC), and gave it a budget of $42 million to get the ball rolling.

I date the start of the modern era of health IT to January 20, 2004 when, in his State of the Union address, President George W. Bush made it a national goal to wire the U.S. healthcare system. A few months later, he created the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC), and gave it a budget of $42 million to get the ball rolling.

The first “health IT czar,” David Brailer, focused on convening stakeholders, banging the drum for computerization, and creating standards for health IT. The seemingly arcane matter of standards turns out to be crucial, since only through a common language and protocols could computer systems have any shot at sharing data with one another (“interoperability,” in IT-speak). This is not a new issue in the world of technology: a protocol known as TCP/IP was central to the success of the Internet. And standards are why your light bulbs and electrical plugs fit into their respective sockets when you bring them home from the hardware store.

Brailer did what he could with $42 million, but – when you think about trying to change the course of the $3 trillion dollar a year U.S. healthcare system – there was only so much he could do. Within five years, however, the ONC’s budget received an injection of new resources, and not a small one: from $42 million to $30 billion. The story of how that happened is an amazing blend of happenstance and opportunism.

In 2008, when Congress passed a $700 billion stimulus package to rescue the economy, it chose to spend the money on “shovel-ready” projects – those whose plans were on the drawing board. Tucked among the highway construction and railroad repair jobs that were funded was a project of a different sort: $30 billion to help the American healthcare system go digital.

In 2008, when Congress passed a $700 billion stimulus package to rescue the economy, it chose to spend the money on “shovel-ready” projects – those whose plans were on the drawing board. Tucked among the highway construction and railroad repair jobs that were funded was a project of a different sort: $30 billion to help the American healthcare system go digital.

Policymakers, concerned that doctors and hospitals might buy the computers with federal money and not use them, attached a very big string to the money: a set of criteria that IT vendors and those buying IT systems needed to meet to quality for the federal bucks. These criteria became known as Meaningful Use.

Let’s take a deep breath and review the state of the universe, circa 2009 – particularly in light of what we know today: that Meaningful Use has become the most controversial, even vilified, policy initiative in the health IT world, perhaps in all of health policy (okay, maybe second to Observation Status and the SGR). In 2009, very few people would have argued that it was a good idea to create a detailed set of government regulations dictating how doctors and hospitals should build and use their electronic health records. But that is precisely what MU has done. Some slopes are, in fact, slippery.

And yet, putting myself in the place of the 2009 decision-makers, I don’t see any villains, or even any particularly egregious blunders. It’s just that things have gone off the rails, which is why we now need to change course.

Okay, back to 2009. The first question: Was it a good idea to use federal money to promote health IT? My answer is yes. In 2008 only about 10 percent of hospitals and doctors’ offices had electronic health records. As long as Congress was spreading $700 billion of federal fertilizer around to stimulate the economy, why not use some of it to rectify this market failure? I think the health IT incentives were sound policy.

Second question: Did we need a set of standards to accompany these incentives? Here, too, my answer is yes. There had been earlier initiatives, mostly by private insurers, in which doctors were given “free” computers and simply put them on their shelves. That, of course, would have been scandalous when scaled up to federal size. So Meaningful Use, as a policy, made sense.

The third question reflects the common complaint that the federal incentives drove the purchase of “immature IT systems” – and that we should have waited until the systems were more mature. Here, too, I’m unpersuaded. A program with a longer timeline would likely not have met the shovel-ready requirement. Moreover, the vendors had been working on their EHRs for decades (Epic was founded in 1979); a couple of years’ delay wouldn’t have gotten the systems any closer to perfection. The only way that health IT was going to get better was to implement the best systems and improve them, guided by insights born of real-life experience.

So, given these facts on the ground in 2009, I believe the policy decisions were sensible. And for a while, everything went pretty well. Meaningful Use Stage 1, implemented in 2010-12, consisted of achievable standards designed to ensure that EHRs were being used effectively. But it was not so prescriptive as to stand in the way of the primary goal, namely, wiring healthcare. Adoption rates soared and MU ensured that the computers were being used.

With Meaningful Use Stage 2 (2012-present), things went sour. The standards became far more aggressive, veering far more  deeply into the weeds of clinical practice. MU now dictated how doctors should give out handouts to their patients (they must be prompted by the computer). It held doctors and hospitals responsible for ensuring that patients viewed and transmitted their data to third parties (most patients had no idea how to do this). It forced EHRs to meet onerous disability access requirements. All of these are noble goals, but all are bells and whistles – the kinds of changes you make after you’ve nailed the basics of getting the darned machines to work safely and efficiently. I spent a morning in June watching Christine Sinsky, a primary care doctor in Dubuque, Iowa and an expert in practice redesign, struggle to survive the regulations. While the ONC’s goals were laudable, she said, meeting the MU requirements had become “like [solving] some riddle or puzzle. Life is hard enough. Why are we making it so much harder?”

deeply into the weeds of clinical practice. MU now dictated how doctors should give out handouts to their patients (they must be prompted by the computer). It held doctors and hospitals responsible for ensuring that patients viewed and transmitted their data to third parties (most patients had no idea how to do this). It forced EHRs to meet onerous disability access requirements. All of these are noble goals, but all are bells and whistles – the kinds of changes you make after you’ve nailed the basics of getting the darned machines to work safely and efficiently. I spent a morning in June watching Christine Sinsky, a primary care doctor in Dubuque, Iowa and an expert in practice redesign, struggle to survive the regulations. While the ONC’s goals were laudable, she said, meeting the MU requirements had become “like [solving] some riddle or puzzle. Life is hard enough. Why are we making it so much harder?”

This July, Karen DeSalvo, the director of ONC, told me that her office was looking to scale back the MU regulations. Jacob Reider, ONC’s deputy director, using a delicious euphemism, also conceded that the MU Stage 2 requirements were overly “enthusiastic.” While I appreciated the forthrightness of the ONC leaders, I wondered whether they would achieve their goal. After all, scaling back is not among the core competencies of government bureaucracies.

This July, Karen DeSalvo, the director of ONC, told me that her office was looking to scale back the MU regulations. Jacob Reider, ONC’s deputy director, using a delicious euphemism, also conceded that the MU Stage 2 requirements were overly “enthusiastic.” While I appreciated the forthrightness of the ONC leaders, I wondered whether they would achieve their goal. After all, scaling back is not among the core competencies of government bureaucracies.

In the past month, both DeSalvo and Reider left ONC. DeSalvo is now the acting Assistant Secretary of Health, taking a leading role in the Ebola response (after announcing she was leaving ONC, the Department of Health and Human Services clarified that she’ll still be involved in its policy decisions, though will no longer have day-to-day management responsibility). Reider simply resigned. In the past six months, in fact, more than half of ONC’s senior personnel – its chief scientist, chief nursing officer, chief privacy officer, and director of consumer eHealth – have jumped ship.

Why? The last of the $30 billion will be spent by the end of this year. While it would appear that ONC will lose its power of the purse, it’s not that simple – the plan has been that, starting next year, rather than receiving a bonus for implementing an EHR that met MU standards, doctors and hospitals would begin seeing Medicare cuts if they didn’t meet them. But with Medicare already slashing payments through a variety of other mechanisms (value-based purchasing, no pay for errors, readmission penalties and the like), many people think that it won’t have the stomach to penalize hospitals and doctors for failing to meet the increasingly unpopular MU standards.

Unpopular is an understatement – the Meaningful Use program has clearly lost the hearts and minds of clinicians and CIOs. As of this month, only two percent of eligible physicians and about one in six hospitals have successfully attested to MU2 requirements. Even former supporters have taken to calling the program Meaningless Abuse. Not good.

In the face of all these challenges, ONC appears adrift, stripped of its resources as it tries to administer a failing program. It’s no surprise that its leaders are rushing the exits.

What should become of ONC and Meaningful Use? The key thing to remember is that MU was an accidental program – one that never would have happened had the economy not tanked in 2008. So rather than trying to salvage it by tinkering around its edges, it is time to rethink the whole shebang. In this, I agree with John Halamka, the Chief Information Officer at Beth Israel Deaconess Hospital and the chair of several HIT policy committees, who believes that ONC should “declare victory” and markedly pare back Meaningful Use.

Declaring victory would not be unreasonable. Against the primary goal of wiring the American healthcare system, ONC’s program worked – the number of hospitals and doctors’ offices with functioning EHRs skyrocketed from 10 percent in 2008 to approximately 70 percent today. The health IT market is far more vibrant than ever before. Even Silicon Valley – which has always given healthcare a cold shoulder – has now joined in the fun, with major health IT initiatives at Apple, Google, Salesforce, Microsoft, and in garages all over San Francisco.

Rather than continuing to push highly prescriptive standards that get in the way of innovation and consume most of the bandwidth of health IT vendors and delivery organizations, MU Stage 3 should focus on promoting interoperability, and little else. Last month, an expert panel presented ONC with a reasonable set of recommendations calling for standardized, publicly available application programming interfaces (APIs), the EHR version of standardized light sockets. This change would allow EHRs to communicate with each other and developers to write apps that could link to the large systems like those built by Epic and Cerner. Promoting this kind of interoperability would be a judicious role for a smaller, less muscle-bound ONC, and for MU Stage 3.

Ending the prescriptiveness of MU doesn’t mean abandoning the goal of using EHRs to improve healthcare. Now that the vast majority of U.S. hospitals have EHRs, the stage is set to promote the outcomes we care about through Medicare’s existing programs – without micromanaging the technology. When Medicare publicly reports adherence to evidence-based practices, hospitals with health IT systems will install decision support to meet those standards. When Medicare penalizes hospitals for excess readmissions, hospitals will create electronic links to primary care clinics and nursing homes. When Medicare ties patient satisfaction to hospital payments, healthcare system will offer their patients access to laboratory results, x-rays, and on-line scheduling, to say nothing of email and telemedicine access to clinicians. When ACOs live or die based on their efficient use of resources, they will implement computer systems that help them conserve resources. It is the outcomes we care about, and hospitals and doctors should be free to use whatever IT tools (or other non-IT strategies) to achieve those outcomes. That’s the best path forward.

By the end of this decade, I believe we will look back on the 2009-2014 era and see government intervention – particularly the $30 billion incentives and the early years of Meaningful Use – as having helped transform medicine, finally, into a digital industry. As our IT systems get better and our processes and culture adapt, this transformation will end up improving patient care and, eventually, saving money, notwithstanding our rocky start.

So today, even as we struggle with Meaningful Use, let’s praise the government for knowing when to intervene. Let’s hope that tomorrow, we can praise it for doing something far harder: knowing when to stop.

* * *

I’ve spent the last eight months writing my book, “The Digital Doctor: Hope, Hype, and Harm at the Dawn of Medicine’s Computer Age.” It is done (and the early feedback has been gratifying) and will be published by McGraw-Hill in the spring. (You can pre-order it now on Amazon if you’d like.) I’ve taken a blog vacation to do the writing, and it’s nice to be back. Thanks for your patience.

As usual, Bob, this is a fine summary. As you might suspect, however, I respectfully differ with you about the role of HIMSS and the ONC is going with standard-less and interoperability-free software. There were also no requirement to address usability and patient safety. I think we could have had a far better set of EHRs if we had insisted on a set of data standards and usability testing by the time the funding was available. The decade-long delays in agreeing on standards was not due to technical reasons, but rather to proprietary efforts, attempts to capture market share and to avoiding allowing hospitals to switch vendors. Call it greed, wise marketing plans, whatever. It was destructive and we live with that failure. Yes, far far more hospitals are now using HIT. But the users are not happy and we don’t have interoperability. We just needed either the industry association or the government (or, hopefully both together) to say no funding would be paid for systems that didn’t meet some minimal data standard (pick almost any from the 5 major winners) and usability testing.

Of course, we all wish you great success with your book and with your life long efforts at improving patient safety.

Thanks, Ross — your thinking has been immensely helpful to me as I have tried to wade through this morass.

I agree with you that government should push harder for interoperability. But I respectfully disagree on usability. If someone had reviewed the plans for Meaningful Use in 2009, they would have seemed benign and unassailable. But then you create an (inevitably) politicized process, with all sorts of special interests — ranging from the vendors to the advocates for various special populations. And a few years later we have an overly prescriptive mess.

Are you really confident that having the government step into defining usability isn’t just a new slippery slope, the kind that led a well-meaning Meaningful Use program to get so deeply into the weeds that its hard to see the fairway anymore? While the market doesn’t work perfectly in health IT (by any means), the track record to date on having the government design healthcare websites (Exhibit A: healthcare.gov) is far from encouraging. As you have persuasively shown, usability must be improved. I just have more confidence in the market doing this than the government.

Gentlemen/Doctors:

I have a 2009 Android cellphone whose OS is out-of-date. Keeping up with technological advancements (from a software perspective) is always challenging AND purchasing new hardware which will make the best use of improvements in hardware and software pose an increase challenge the health care stakeholder. Transparency, from an interoperability perspective is the latest challenge that from my amateur perspective, is simple. One only needs to know who is making a request and what device is the host receiving it. Afterwards, fulfillment of the request should be a simple matter (provided the host can handle the request). These issues take investments of time, money, and expertise. Good luck to you and happy new year 2015!

Bob,

Your post is a simple historical perspective on a formidable abuse of doctors, nurses, and patients who have served nobly in these experiments promulgated by the vendors and the Congress of the United States.

What is there to show for this? Dead patients who otherwise would not have died when they did, new errors, sending a 5+ sick patient (with Ebola) home from an ER, increased overall costs of care, and no improvements in outcomes, in addition to a daily litany of near misses and delays in care. How could you omit the now defunct famed CCHIT child of HIMSS that gave Congress the notion that these systems were safe?

What is particularly disturbing and disheartening to me is your support of experimenting on the patients without their consent, embodied in your statement: “The only way that health IT was going to get better was to implement the best systems and improve them, guided by insights born of real-life experience.”

Which are the best systems and how is that determined when there is not any surveillance of them?

Circling back to your statement, that is not what the Federal laws protecting patients from dangerous medicines and medical devices state.

Best regards,

Menoalittle

Lost in all of these hypotheticals is a fact that these systems are not any different than other medical devices except that the other medical devices go through robust evaluation that tests safety, efficacy, and usability. The usability is so poor on the currently available systems that they would all have problems assuring the FDA that the error prone design is approvable. About safety and efficacy, there is little data about the adverse events, crashes, lost data, and misidentifications to determine worthiness of approval.

Bob,

This was a great article. I have to comment on a few things.

1. The market was moving towards EHR, albeit more slowly, but the artificial MU market caused a mad dash to EHR. And with all the incentives, blind squirrels were finding their bonus checks. You could feel the air getting sucked out of the room with MU rules and diving for incentives at EHs and EP offices. This artificial market lead EPs and EHs down a terrible path. They felt if the EHR was certified, it must be usable and safe. And in NO way was that the case. ONC touts all these MU1 users as a success, but its hardly that. Its a false market that has now crumbled.

2. If anyone actually watched different users work the same EHR, you would be amazed at the inefficiency, the rapid fire clicking, ignore popup ignore ignore ignore,the “ whatever “comments that fly. EHRs near miss and many times daily and sometime full on make disasters happen daily. Yet someone please tell me how to easily report these near misses or full on disasters via the EHR. There is no easy way. Among the 300 other rings we are supped to be doing, we are to memorize the patient IDs and what happened and get back to our computer and email some quality person and hope for a response? Never happens. If EHRs are so great, how come over the past 6 years we haven’t been bombarded with study after study on how much less money is spent on patient care, how much more safe it is via EHR, how great EPs and EHs and nurses love using them?

3. Its really time for MU to be killed not die. Right now its dead they just can’t read their own data. You are right MU 2 killed it. Not a single soul at ONC or CMS will just come out and say it. Every month we get deceptive presentations on MU program out of ONC on “look how many have signed up in 2008” and “oh, the MU2 can’t be assessed yet, even though the numbers are tepid” Pure government deception.

4.MU penalty phase will ice the program. ONC and CMS really think penalties will encourage people to spend big bucks on EHRs? Yeah, wrong. Penalties never has worked before, won’t work now.

5. Its time for MU to get out of the way of vendors so they can focus on usability, safety and security.

Forget prescriptive MU attestation.With at least 5-10% of EPs getting audited and 20% of Ehs and the very high failure rate of audits of EPs, where they take back all your money and then audit you every year for life, you are really better off just getting out of the program. The audit process is about as dark as any government audit program can be and there are many stories out there of real audit nightmares. Just that alone will drive EPs out of MU.

6. EPs are currently getting run over by overly complex, over reaching and overlapping government programs, not just MU but PQRS, VBM, upcoming ICD-10, etc. Its a disaster. Good luck asking for help from CMS about them. As an aside for ICD-10, that should be phased in. Why not? CMS can’t program that? Every eclaim and HCFA 1500 can tell you if the codes are 9 or 10. Why not let us dip our toe into the system. Why the on off data? Did CMS not learn one thing from the failed ACA rollout? I can tell you that OH BWC will not be doing 10 codes and so we will have to keep both sets to practice. Why not have CMS allow both to make sure that the claims get processed and people get paid, not from just CMS but also private payers. Sorry I digressed. But you can see that MU is just one of a bunch of headaches for the average EP.

Again, I loved your article thanks for stirring me up at 3 am!

Dear Bob, welcome back!

I totally agree with the previous comment, among all “health technologies” IT seems the only one that doesn’t need any assessment before, or even during, its implementation in every day practice…

During the last EUnetHTA conference in Rome, I discovered that the MAST programme, addressing the assessment of e-health technologies, covers only telemedicine!

I agree that we should expect some benefit to organisations and patients from IT system, but I’m really unsatisfied when I look at something driven only by market and legislative issues, without any consideration of effectiveness. Even if costs could appear quite small, compared to the whole health expenditure, it should be noted that they are acquiring more relative weight in shrinking health budgets, in Countries like Italy.

So, thank you for the attention you pay to these issues, I’m looking forward your new book!

Best regards,

Gaddo.

Only the government would create a fiasco like this. The notion of healthcare IT and EHR is a good one. The problem is the brain-trust at the top of the food chain, never gave much thought to (and probably didn’t care) that none of these EHR were ever going to interface with one another. I mean…in the perfect world – wouldn’t it make sense that patient A could be on vacation in Philadelphia ( their record in their primary care physician’s practice in Spokane) and require treatment and have that treatment facility be able to see their actual chart 3000 miles away?! Don’t even get me started on the vendors who made bank on this deal.

It would have been nice if the author took this a step further to mention what the government is doing with all this patient information. While PHI and HiPPA are alive and well – no one talks about how secure their information really is. Congress nor the Administration have no clear definition of what “privacy” even means. These EHR products contain no mapping tools to tell you when your information was access and for what purpose. I know this is a bit off-topic, but if we’re going to talk about EHR’s and MU, it would be disingenuous to NOT talk about the effects on patients. Shouldn’t patients be considered in all of this?

I encourage people to read Dr. Deborah Peel’s works on this subject matter. Her fight to ensure that patients have the ability to control how their sensitive health information is being used, cannot be overlooked.

“I agree with you that government should push harder for interoperability. But I respectfully disagree on usability… Are you really confident that having the government step into defining usability isn’t just a new slippery slope…usability must be improved. I just have more confidence in the market doing this than the government..”

Respectfully Bob, this misses the point around usability of systems and supports the red herring argument put forth by vendors.

It’s a far different proposition for the government to mandate the design of Certified EHR products (e.g. Certified products shall display patient demographic information in comic sans font, 14 points, in the top left corner of each screen with the following format) than for the government to require that Certified products adhere to some minimum level of usability testing following standard, rigorously developed protocols. And with a narrow focus on usability issues most likely to impact patient safety.

Oddly, such a protocol exists: (NISTIR 7804) Technical Evaluation, Testing and Validation of the Usability of Electronic Health Records: http://www.nist.gov/manuscript-publication-search.cfm?pub_id=909701

As do many other resources developed in conjunction with luminaries in the field of human computer interaction that vendors (and healthcare organizations) could have used to make their products more usable (and safer):

http://www.nist.gov/healthcare/usability/index.cfm

What finally made its way into certification was a requirement that vendors post the (supposed) results of summative usability testing of certain functions of their products (i.e. safety-enhanced design) but WITHOUT any kind of standard protocol (e.g. NISTIR 7804) or external evaluation of the results to ensure that the testing was done rigorously, the results are meaningful and comparable, and that products that have demonstrated residual safety risks (per the vendors’ own testing) don’t reach market.

The result, of course, is that many systems and implementations of systems fail to meet even basic standards of usability (of the type that the FAA, FDA, NRC, DoD and other federal regulators require) and – perhaps worse – purchasers of systems have little or no rigorous data on which systems are more usable and more safe.

Ron

The greatest fallout from the headlong rush into electronic medical records may be the demise of the hospital progress note. Years ago, one could open a chart, flip through a few pages, struggle a bit with the handwriting, but come out with a pretty good idea of what the doctor thought was wrong with the patient and whether or not it was getting better. Today, one must scroll through page upon page of data, fully legible, but copied over from other sections from the record, in hopes of finding a few words that actually reflect the doctor’s thought process. This is often impossible to find, or it was copied from yesterday’s note, which was copied from the day before, and the day before that…Bob, as a leader in academic medicine, it might be a good time to stand up for progress notes that actually show progress.

My grey hair attests to my peripheral involvement with the introduction of EMRs as a user ….I knew things were not on track when the first EMR I encountered emulated the paper record literally using the same tabs that are found in every paper medical record. This was at the time when we (providers) were just getting used to integrated progress notes where we could finally review the clinical narrative of the patients progression of care as collaboratively documented by the team without having to wade through every section of the chart. When I encountered my first EMR they were large repositories with different views for different clinicians – the concept of collaborative documentation was lost. In my opinion, this ‘modularization’ is what led to the fiasco at Texas Presby and is the reason why so many providers find the current wave of EHR vendor offering of little value.

To some degree I agree with all of the comments. But, we should be looking at the elephant from the other end as well.

What, was usability and safety like with the paper chart? I am not convinced it was any better when you waited a few days for a note to be dictated and the most recent information was not in chart for the most active patients since the chart never made it back to the Medical Records Department.

One of the problems with EHR’s is the insistence on trying to keep a paper paradigm in an electronic system. Why replicate the data into notes multiple times? The EHR’s do not require this, it is an implementation decision. I know organizations that built into the EHR workflows the requirement that the same information is recreated in a new note for each department.

It is easy and convenient to blame the mess on the government. Resistance to changing organizational structures and workflows has led to more and more prescriptive bureaucratic responses.

EHR have great promise, and who can argue with seeing an X-ray after its ordered or viewing notes all in the same place or placing an order on any computer. I agree there. BUT! The government made a HUGE mess of it. Its not a resistance to change, many of us use a non certified EHR or an EHR that we are not attesting to meaningful use. It would me MUCH better if everyone could just view the labs, history etc, and add our thoughts and plans instead of 10 pages of prior meds, current meds, social history, current and past problems, allergies, risks, etc. just to get paid by the government or payer. Remember the old days when it would be like an entry in a journal, 3 lines of what is happening now. How EASY it was to understand what was going on, what was the current issue, etc. Not its a firehose of useless information. I challenge anyone to log onto a hospital EHR now and tell me in less that 10 minutes why they were admitted, what are the issues now, etc. Its a giant mess. I am NOT saying go back to paper, we need to move on to USABLE SAFE and SECURE EHRs. Not the awful things we have now, and MU is definitely the culprit.

@gable

Paper=contemporaneous, ease of comparison of multiple points in time, different shape to the handwriting so as to easily recognize the author, ease to distinguish between the attending and the housestaff or paraprofessionals, who wrote the order, etc.

Digital=gibberish, ease to see lab data

Both=no search function, but easier to find progress note of relevance on paper.

The usability problem is easily brushed aside by people who dont actually have to see patients and enter data. But this is a huge drag on efficiency. And it has never demonstrated superiority in any metric. Physicians are taking money to allow know nothings and do nothings to make these changes. But where are we running? A word document contains digital records, is highly usable, and can be stored on a central server. That’s what I had 8 years ago. Now, hundreds of government dollars later, I have a useless POS EMR which isn’t that much better. And the purpose of this has never been clearly explained.

What is the benefit to patients, to practices, or to physicians? So far: errors and loss of efficiency for patients, practices with INCREASED overhead (our IT guy is essentially a fixture in our office), and doctors who are burning out, far behind, joyless, balancing data entry against being human. It is easy to dismiss this as growing pains. But I see this as a sign of a dead end. My partner says we will never give up the EMR. Perhaps this is true, but we haven’t gotten anywhere yet. Healthcare in America is still messed up, and EMR’s are not taking us out of it.

On New Year’s Day, my dear friend and Practice Manager, Debbie Tichenor, RN passed away at her home, quietly and unexpectedly. Healthcare has lost a tremendous ally. One of the last emails I received from her was her response to my question “What are your thoughts?” in regards to this “Meaningful Use” article. Debbie’s thoughts were poignant, honest, and astute and deserve to be shared. Thank you for this forum.

*

December 18, 2014:

I agree totally. Government supported incentives that assisted healthcare facilities and physicians with conversion to EHR systems were reasonable by assisting to offset the huge implementation costs. Stage 1 basically confirmed the provider’s adoption of EHR and promoted physician discussion of some public health care concerns such as alcohol, tobacco, and illegal drug usage. In Stage 1, EHR users collected health information in a more uniform manner with the potential to be shared with other physicians and facilities. EHR’s assisted with the issue of reading and interpreting hand written notes. These are positives and not hard to attest in Stage 1 MU.

Stage 2 MU is mired in government bureaucracy and does not necessarily promote improved patient care. A great deal of time and effort is required in an attempt to understand and meet the requirements. The development of the patient portal is one of the most useful byproducts of the EHR; however, in Stage 2, providers will be punished if patients do not show participation. Though the percentage required to meet this measure in relatively low in Stage 2, it will increase going forward. Percentage requirements have increased from Stage 1 to Stage 2 for all measures. I agree that MU should be scaled back and not directly affect the provider’s reimbursement.

In my opinion, the overall motive for the EHR adoption seems geared more toward data collection and not necessarily improved patient care. My concern is this DATA COLLECTION will be used in the future to determine IF health care coverage will be attainable and/or affordable for the individual especially as the move toward a one payer system looms on the horizon. For this reason alone, scaling back on government mandates and bureaucracy as it pertains to EHR development, adaptation, and utilization may be difficult.

“Hard to kill a monster once it is created.”

Debbie Tichenor, R.N.

Practice Administrator

Murphy Pain Center

Thanks so much for sharing this, James, and I’m sorry for your loss. She sounds like quite a thoughtful and caring person.

— Bob

With all due respect for Ms. D. Tichenor, RN, Stage 2 of the MU program, the data that will be aggregated will compile a metadata database to facilitate understanding of current efforts used in patient care with the objective of seeking patient care improvements while attempting to cut the costs of care delivery. As Atul Gawande stated in a recent interview by Robert Wachter, MD1, “Information is our most valuable resource, yet we treat it like a byproduct. The systems we have…are not particularly useful right now in helping us execute on these objectives. We’re having to build systems around those systems.”

Wachter, R. (2015). My interview with Atul Gawande [BOOK REVIEW, GLOBAL HEALTH, HEALTH POLICY, HOSPITALISTS/HOSPITAL MEDICINE, INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY]. Wachter’s world (Jan 6, 2015). Retrieved from http://community.the-hospitalist.org/2015/01/06/my-interview-with-atul-gawande/

Are you sure?

Big Data is “a fickle, coy mistress,” inviting, yet not without risk.

~ per Alexei Efros, a leader in applying Big Data to machine vision

http://www.newyorker.com/tech/elements/steamrolled-by-big-data

I love “big data.” And like some readers here, I’ve been crunching big datasets for over 40 years. With EHRs we can collect more information on more patients in very convenient ways (ignoring the 6 minutes of annoying data entry by physicians for each visit). That’s wonderful. But like a child with a hammer, we must learn that not everything we think is a nail is in fact a nail. There are millions of spurious correlations that any fool with SPSS or SAS will find — that will turn out to be distractions rather than insights. Direction of causation is often unclear; lack of data standards make cross system comparisons treacherous at best, down right deceptive at worst. Yes, we can all benefit fabulously from big data, but analyses require the same level of understanding and insight we expect from brilliant diagnosticians or deeply skilled social scientists. Ross Koppel, Ph.D., FACMI

Agreed.

Conscientious and rational application of research methodology (i.e.,evidence -based practice), statistics, and clinical practice to big data should better inform medical science. The patient is not a number but nevertheless lie within the mean, or standard deviation from the average compared to the members of the cohort. Moreover, enlightened medical practice, to my mind, will be less biased or confounded by such criteria as sex, race, or ethnicity. These variables should be accounted for in the study samples.

Well said, Bill.

Big data is like the cacophonous notes of an orchestra warming up before a concert… When focused, purposed, and inspired to achieve goals beyond the summation of its parts (or bytes), the result is music no longer subject to measure – it becomes art, beauty, healing.

I very much appreciate your concurrence, Dr. Murphy. As I am not a clinician (medical doctor, specialist, or therapist, but an administrator), I cannot address how well “big data” can or will inform the provider. Yet, I firmly believe that a dispassionate critical review of research data will provide better “facts” to help them discuss treatments with their patients that will more likely yield the anticipated and better outcomes. Moreover, those treatments that provide little evidence of benefit yet are costly can either be reduced or eliminated all together. Furthermore, innovation and more useful approaches will very likely develop in the future, as we have seen more frequently in the decades past.

[…] and a little more understandable for people. If you’re a practicing doc, the RUC and Meaningful Use and the SGR – these are abstractions. But when someone says the ergonomics of your everyday […]

I speculate that the casualties of Meaningful Abuse are enormous and unmeasured, many excellent physicians retiring prematurely, the stress and cost of implementing these unattainable useless requirements, the valuable time of healthcare providers diverted to trying to achieve these requirements at the expense of patient care… yes, a lot of casualties. My 80 year old Medicare patient is not a light bulb, she is a person who wants me to listen and care for her, explain and discuss her medical issues and treat her with all the knowledge and expertise as her healthcare provider. Quality patient care is not measured by “meaningless use” requirements but is a patient physician relationship which is being eroded by Meaningful Use requirements. It’s time for it’s funeral. It’s eulogy is “a major achievement in the expansion of the EMR system in the healthcare industry” ….we just won’t mention the casualties.

Dear Dr. Murray:

As an administrator, I wholeheartedly agree with the thrust of your commentary. However, the purpose of the subsidies were to help physicians modernize their care by fully digitizing it so that information would be readily available and that, hopefully soon, care coordination through interoperability, would make total patient care more seamless and less error-prone. However, I do agree that the burden of demonstrating use and usefulness may have placed care providers under greater stress but the promise of greater benefits to stakeholders is the ideal that we all hope to strive for and realize.

Thank you for your understandable and appreciated perspective.

Sincerely,

Bill J. Adams

Mr. Adams,

You missed the point. Typing and templates consume time and pigeon-hole patients into templates that do not reflect their true medical condition. The time spent typing compliant notes is time not spent on taking care of the patient.

While transmitting information seems like a lofty goal, if it takes too much time and is inefficient, it does hurt patient care. It’s time for the government and administrators to admit physician time is valuable and should not be spent on doing clerical duties.

I am Katherine, a MSM Healthcare Administration student from SNHU. Prof. Duffy, from the Err, Sci, Risk & Disclosures course, brought me to your website, she mentioned about you, Robert Wachter MD, in her lecture. Your article, ‘Meaningful Used, Born, 2009, Died, 2014?’ has caught my eyes. I have been following the development of the EHR Incentive Program since the beginning of my MSM program, three terms ago, for both academy and business reasons. I am glad that you brought up this topic and talked about it. For me, I don’t know if ‘Died’ is a right word to use or not : ) But, I am sure there are still lots of challenges ahead. I feel that some of the government agencies that involved are loosely organized. Besides, the techies and the healthcare professionals are being trained differently, having different backgrounds and work experiences. They even speak different languages sometimes. I hope things go well in the future, and everyone can benefit from it.

In reading this excellent article and discussion again I am still struck by your concise assessment of a multi-generational problem: “scaling back is not among the core competencies of government bureaucracies.” This ability to scale back is difficult when we put so much time into something and the sustained monetary flow to a department or organization in question is dependent on a static condition for its existence and survival. My father was always looking for that kinetic energy which could transform life and work into something that it was not. So, your article made me recall the quiet thoughtful teaching my father gave me.

I recalled in your words, Bob, some of the wisdom of my father who was a genuine searcher for what is true and how to actualize it like you. This talk of scaling back is something I heard from my father often as a boy when he expressed similar questions and frustrations to me after coming home from his government position and just being quiet with me. I was my father’s only ally and although very young I became his counselor/listener. How simple things were then so many years ago. The past almost seems like a fairy tale world full of enchantment before all the technology and mind bending that haunts us today. Bob I do hope you get the chance to enjoy nature often in its wild form. I grew up in California and wish you well in your quiet walks when you can scale back the mind and just be with, Bob. Love your website. It is like a good walk through the forest or mountains.

I agree with the direction of Ross Koppel’s response to Bob Wachter’s column “Meaningful Use. Born, 2009, Died, 2014?” (11/13/2014), and I believe it can be amplified in some respects. I think it’s clear that the problems with EHRs that have been sold and implemented in providers’ offices and facilities can be traced to political and financial decisions that then had their effects on technical decisions. The government completely absconded from its responsibility to define vendor- and technology-independent data and interoperability standards for a product they (e.g., the taxpayers) are paying for, but rather “approved” self-appointed medical-industrial complex players to “define” EMR certification “standards” for implementation and communication. It’s no wonder they left it to the industry. David Brailer himself is a HIT services vendor. Then there were the demanding presences of Newt Gingrich and Tommy Thompson (both are federal and state HIT vendors) and Tom Daschle and the rest of the legal/lobbying community who lobby their old “contacts” in the government on behalf of their own HIT clients. There are published data showing that during the Bush Administration, private sector contractors and contracting companies outnumbered career civil servants in the Executive branch (it wasn’t just in the military). Anybody who has worked in the private sector knows that companies don’t share their “trade secrets” and “proprietary standards” with the public or with each other (if they did, selling “business intelligence” and “industrial intelligence” wouldn’t be such a lucrative field). The wonder is, knowing that, how people such as public policy-makers could continue to do the same things and expect a different outcome.

Doctors claim that they understand “technology” and “medical devices” and “information systems,” even though they don’t seem to based on their own comments and reactions to events and public policies. For example, many surgeons, as a matter of policy, leap into using bleeding edge technology while being trained “on the job” (i.e., using their patients as guinea pigs) without simulations practice first–while the non-medically trained vendor at their elbow is telling them how to use it on the particular patient on the table. I am troubled by clinicians’ (even those who call themselves “informaticists”) misunderstanding of “standards” as they relate to IS/IT. As an example of “the government” “micromanaging the clinical encounter” by promulgating “standards,” Wachter used the example of dictating what kinds of communications clinicians should have with with patients. This may be a “clinical practice standard”, but it has nothing to do with IS/IT standards as they relate to how systems are designed, developed, implemented, tested, and fielded–or with the discussion of interoperability, data standards for shareability of patient information, technical policies like meaningful use, etc. In fact, the requirement for how and when clinicians SHOULD communicate with their patients is based on the evidence from a ton of quality improvement, root cause analysis, shared medical decision-making, and patient safety research from all over the world (for example, that doctors in the US interrupt their patients on average within 18 seconds of the beginning of the encounter while their patients are telling them about their signs, symptoms, reactions to medications, etc.). There are many requirements in the “meaningful use” category that are based on quality improvement, root cause analysis, shared treatment decisions, and patient safety research and evidence; but they are not related to data and processing standards for information systems, whether for EMRs, CPOE, HIT, or any other technology-specific or industry-specific implementations. It appears that clinicians are using technical system development and deployment requirements (about which they know little) as a proxy (or an excuse) for their discomfort and anger that they are “being told what to do,” as they perceive it, in the clinical realm (about which they claim to know a lot, even when they conflate “evidence-based clinical practice standards” and “IT/IS standards”). To pile irony upon irony, many of them would claim that they support the aims and practice of evidence-based medicine, while complaining about “cookbook medicine” (e.g., a recipe IS a “standard”). However, we are trying to move away from the bad old days of cottage industry medicine, guilds of barber-surgeons and their apprentices (“see one, do one, teach one”) and clinical hierarchies of doctor/priests with exclusive divinely-inspired access to arcane knowledge.

It’s difficult to get doctors, even those who are titled “Directors of Medical Informatics” in hospitals and academic medical facilities, interested in the most basic kinds of standards which Dr. Koppel alluded to in his comment: data standards and interoperability (shareability) standards, as designed into requirements documents such as data models and process models. (Believe me, I’ve tried). It’s useless for them to complain that “EMR vendors don’t support clinical workflows.” No clinical systems purchasers ever tell the vendors what their organizations’ information and process requirements are, let alone what new service levels should be met and implemented based on the outcomes of their internal quality improvement and RCA studies. The way they hire their vendors and their in-house IS/IT staffs makes that outcome baked-in. As Don Berwick said, “Every system is perfectly designed to achieve the results it gets.” A RAND study in 2013 (the one that Congress people got so exercised about) indicated that more than half of the meaningful use money went to Epic (the other major vendor is Cerner)–so what incentives do they have to promote interoperability, data standards, reporting standards, processing standards, etc.? Vendors are hired based on who they are, whom they know, and whom other competing facilities are hiring. Internal IT staff are hired for their experience with Epic (or Cerner, or some other explicit technology implementation), not for their knowledge and experience in developing and maintaining information systems in organizations. Therefore, for clinicians to be “shocked, shocked!” that proprietary standards remain and inter-operability is non-existant is either childish or churlish, along with their manufactured “anger” when “the government” steps in to protect the taxpayers’ investment. To make their weak argument even weaker, the doctors engage in the logical fallacy of using the example of healthcare.gov as “proof” that “the government” doesn’t know how to develop systems, rather than the example of agencies that do require data and processing standards to be implemented, such as the FAA and other agencies that a responder listed (or even NASA, which was able with its standardized systems to land a person on the moon).

The issue of “progress notes” is also a red herring, which doctors use to imply that their service delivery practices would all be safer and of higher quality if they could only read them in their EMRs. There are (at least) two problems with this argument. For one, there is research showing that less than 20% of attending doctors and residents read nursing notes, while 92% of them read other doctors’ notes exclusively. This was true before with paper records and it is true now, even though everybody (doctors and nurses) has access to both in EMRs. Why do doctors claim that they would practice medicine, oh-so-much-better, if only their electronic systems would support what they used to do with their paper systems? The other problem I find with this argument is that it is clear from the comments to this column (and many others that have appeared on websites, listservs, and many other venues) that they are still resistant to treating their patients as whole people rather than as the context-less signs and symptoms of interest to their specialties and sub-specialties. As a patient as well as a person with professional backgrounds in both information systems and public health, I am especially offended by the doctors who opine that there is a lot of “unnecessary patient data” that they have to wade through. IMO, there is no such thing as “unnecessary patient data,” such as updated histories, allergies, lab test results, orders from other providers, perhaps in other facilities, whom their patients see–information that might have a bearing on their current treatment decision-making and how their patients comply or don’t comply with their orders; as well as other information that might hold clues to the social determinants of their patients’ health status, health behaviors, and treatment outcomes. The same question holds: Why do doctors claim that they will provide health care services of improved/higher quality and safety if only their electronic systems would “allow” them to deliver the SAME level of health care services that led to the IOM’s report “To Err is Human”, later IOM reports, and the rest of the global compendium of research and evidence on high-reliability organizations, safety science, all the flavors of quality improvement schools of thought, zero-defect processes, patient safety, etc., etc., etc. Not to mention the same level of care that produces even higher numbers (latest estimate is as much as 440,000 per year) of preventable medical errors, of which at least 30% of medical errors are attributed just to diagnostic errors) even though utilization of medical care (the denominator) has been declining in the US in the past couple of years.