Andy McAfee is the associate director of the Center for Digital Business at MIT’s Sloan School of Management. He is also coauthor (with his MIT colleague Erik Brynjolfsson) of the 2014 book, The Second Machine Age: Work, Progress, and Prosperity in a Time of Brilliant Technologies, one of my favorite books on technology. While he sits squarely in the camp of “technology optimists,” he is thoughtful, appreciate s the downsides of IT, and isn’t overawed by the hype. In the continuing series of interviews I conducted for my forthcoming book on health IT, The Digital Doctor: Hope, Hype, and Harm at the Dawn of Medicine’s Computer Age, I spoke to McAfee on August 13, 2014 in a restaurant in Cambridge, Massachusetts. I began by asking about some of the general lessons from today’s world of technology and business that have implications for healthcare.

s the downsides of IT, and isn’t overawed by the hype. In the continuing series of interviews I conducted for my forthcoming book on health IT, The Digital Doctor: Hope, Hype, and Harm at the Dawn of Medicine’s Computer Age, I spoke to McAfee on August 13, 2014 in a restaurant in Cambridge, Massachusetts. I began by asking about some of the general lessons from today’s world of technology and business that have implications for healthcare.

McAfee: Our devices are going to continue to amaze us. My iPhone – it’s a supercomputer by the standards of 20 or 30 years ago. Right now, hundreds of millions of people carry a device that is about this powerful. Wait a little while. That number will become billions. And those devices will spit out ridiculous amounts of data of all forms, so this big data world that we’re already in – that’s going to accelerate.

Since data is the lifeblood of science, we’re going to get a lot smarter about some pretty fundamental things, whether it’s genomics or self-diagnosis or how errors happen. Then, because we’re putting all this power into the hands of so many people all around the world, it seems certain that the scale, pace, and scope of innovation are going to increase.

So I’m truly optimistic for the medium- to long-term. But the short-term is going to be a really interesting, really rocky time.

RW: When you say medium- to long-term, how many years before we get to this wonderful place?

AM: Don’t hold me to it. But within a decade.

RW: We always like to think we’re special in medicine. We’re so different. It’s so complicated. Do you see any fundamental differences between healthcare and other industries that will shape our technology path?

AM: There are two main things that might retard progress in medicine. The first is healthcare’s payment system, particularly how messed up it is trying to match who benefits versus who pays. The other thing is the culture of medicine. I understand that it’s changing, but there’s still this idea that “how dare you second-guess me, I’m the doctor.”

RW: But we can’t be alone in that. I’m sure many industries have their stars – supported by their guilds – who think, “We’re at the top of the heap, with high income and stature. We’re going to fight this technology thing, since it could erode our franchise.”

AM: Sure, but in the rest of the world eroding the franchise is what it’s all about. It’s Schumpeterian creative destruction [the theory advanced by Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter – it is, in essence, economic Darwinism, and forms the core of today’s popular notion of “disruptive innovation”], so if you’re behind the times and I’m not, I’m going to come along and displace you and the market will speak to that.

I asked McAfee about some of the negative consequences of technology I explore in my book, particularly the issues of human “deskilling” and the changes in relationships – for example, the demise of radiology rounds because we don’t have to go to the radiology department to see our films anymore.

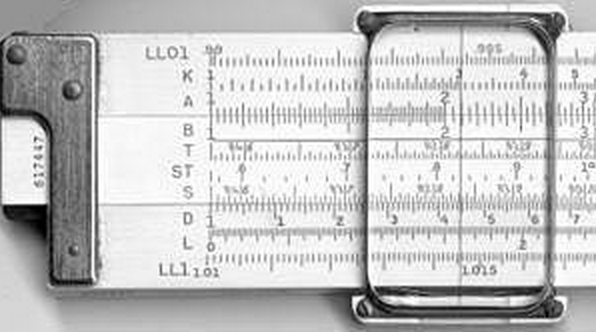

AM: Technology always changes social relationships and it often leads to the erosion of some skills. The example I always use is that I can’t use a slide rule. I was never trained to do that. Whereas engineers at MIT a generation before me were really, really good with their slide rules.

AM: Technology always changes social relationships and it often leads to the erosion of some skills. The example I always use is that I can’t use a slide rule. I was never trained to do that. Whereas engineers at MIT a generation before me were really, really good with their slide rules.

RW: Are there other industries in which people are now smart enough to say, “This is likely to be the impact of this new technology on social relationships, and here is how we should mitigate the harm”? Or do they just implement, see what happens, and then ask, “What have we lost and how do we deal with that?”

AM: Much more the latter. I haven’t seen a good playbook for “here’s what is going to happen when you put this technology and therefore do these three things in advance.” It’s much more that you have some thoughtful people saying, “Wait a minute. We used to do X and we kind of liked that and now we do less of X, so it’s turned into Y. We need to put some Z in place.”

RW: Does Z tend to be some high-tech relationship connector?

AM: In some cases, yeah. But there’s the story about the call center that was unhappy about some aspects of its social relationships. They just moved the break room and the break times so that people literally would just come and hang out a lot more. That made people a lot happier and it made the outcomes better. Sometimes the fix has a tech component, and sometimes it doesn’t.

As in many of my interviews, we turned to the question of whether computers would ultimately replace humans in medicine. I described a few situations in which physicians use “the eyeball test” – their intuition, drawn from subtle cues that are not (currently) captured in the data – to make a clinical judgment.

AM: The great [human] diagnosticians are amazing. But we still pat ourselves on the back about them far too much and we ignore or downplay or we think that we are exceptions to the really well identified problems of this particular computer [McAfee points to his brain]. The biases, the inconsistencies, the fact that if I’m going through a divorce or I have hangover or I’ve got a sick kid, so my wiring is all messed up.

Have you ever met anyone who thought they had below average intuition or was a below average judge of people or they were below average in recognizing sick patients? You’ll never meet that person. We have a serious problem with overconfidence in our own computers.

While severing the human link would be a deeply bad idea, much of what we currently think of as this uniquely human thing is in fact a data problem. The technology field called machine learning – and a special branch of it called deep learning – is just blowing the doors off the competition. We’re getting weirdly good at it very, very quickly.

In addition, my geekiest colleagues would say, “Okay. You think you’ve started data collection for this situation? You haven’t even begun. Why don’t we put a high def camera on the patient? For every encounter, we can assess skin tone. We can code for their body language. Let’s put a microphone in there. We’ll code for their speech tones.”

And then we’ll see which patterns are associated with schizophrenia, diabetes, Alzheimer’s. We’ll do pattern-matching on a scale that humans can never, never equal. In other words, our IT systems don’t care if the guy went to the intensive care unit two hours later or was diagnosed with Parkinson’s 20 years later. Just give us the data.

RW: How much of healthcare will be in the hands of patients and their technology? How much are they going to be monitoring themselves, independent of doctors or hospitals or other traditional healthcare organizations?

AM: It’s hard to imagine how that won’t come to pass. They’ll monitor the hell out of themselves. They’re going to have peer communities that they probably rely on a lot and they’re going to have algorithms guiding their treatment or their path.

I turned to the question of diagnosis, and particularly the issue of probabilistic thinking. The context was the 40-year history of predictions that computers would ultimately replace the diagnostic work of clinicians, predictions that, by and large, did not pan out.

RW: In medicine, there’s no unambiguously correct answer a lot of the times. It’s a probabilistic notion. I call something “lung cancer” or “pneumonia” when the probability is above a certain threshold, and I say I’ve “ruled out” a diagnosis when the probability is below a certain threshold. Setting these thresholds depends on the context, the patient’s risk factors, and the patient’s preferences. I also need to know how accurate the tests are, how expensive they are, and how risky they are. And often the best test is time – you decide to reassure the patient, not do anything, and then see how things go.

AM: Yeah. That complicates the work of the engineers. Not immeasurably, but it does make it a lot more complicated. But I imagine that there are a bunch of really smart geeks at IBM’s Watson eagerly taking notes as guys like you describe these kinds of situations. In their head they’re thinking, “How do I model all of that?”

Bob,

You and he are both weak on the negative consequences of technology, which nay be trivial for word processing, but not for patient care.

For someone pushing MOC for doctors, there is a degree of hypocrisy in your embracing technology that may do more harm than good, a concept that you and your tech brothers fail to assess with the data (because the data about harm is not being collected).

Thank the ONCHIT and HHS for that.

Best regards,

Menoalittle

[…] Bob Wachter, who is one of the founders of the Society of Hospital Medicine and the hospitalist movement, has a great blog called Wachter’s World. Here’s the latest post, an interview with Andy McAfee, self-tagged “technology optimist” and associate director of the Center for Digital Business at MIT’s Sloan School of Management. It’s a terrific conversation about the intersection of tech and humanity, in medicine and elsewhere. “My Interview with ‘Technology Optimist’ and 2nd Machine Age Coauthor Andy McAfee“ […]

Really great interview. Thank you for sharing.