As you can see, no glamour shots for this month’s post. I knew it would come at some point, and my first hospitalization related to my CLL came in a big way in mid-July. Given my interest in global health, it was only fitting that I managed to get sick while out of the country.

The plan for July had been to help teach our Asian Clinical Tropical Medicine course in Bangkok, Thailand and Siem Reap, Cambodia for two weeks, followed by a much-needed family vacation. I felt well during the course, but at the very end of it I noticed I was really tired. We enjoyed 2 ½ days visiting Angkor Wat and other sites in Cambodia, then headed to Chiang Mai, in northern Thailand.

Initially, I thought I was just tired and out of shape, chalking it up to working with the course, travel, etc. Maybe it was something I ate… The four flights of stairs up to our guesthouse room seemed a lot longer than I expected them to be. The next morning, I was even more tired, so my wife and son left to do some touring around Chiang Mai while I stayed in the room and rested. Maybe a nap would clear things up. After looking in the mirror, I noticed that my color seemed a little off. I was hoping that it was just the fluorescent light, but my color looked pretty sallow. And was it just me, or were my eyes yellow?

I tried denial for about 30 minutes, but when that didn’t work I started the self-diagnosis cycle: 39 year-old male with CLL with fatigue, shortness of breath, and jaundice. Being a resourceful guy who had been to Chiang Mai before, I had already identified two possible hospitals I could go to for care if needed. I called Changmai Ram Hospital and asked if I could just check my own blood tests. They were happy to oblige (since I was paying out of pocket). After registering, I paid about $45 total for a CBC, a liver panel, and electrolytes. That is when I found out that my hemoglobin, which had been over 13 a week before, had dropped to 7.6, with an indirect bilirubin level of 5. Anyone who guessed hemolytic anemia as the diagnosis gets the gold star. My own immune system was attacking my very own red blood cells. How rude!

Ironically, I could have developed this exact same complication in the Twin Cities. I may have developed it even if I had not done all the travelling to Thailand and Cambodia. But this did present an interesting management question – NOW WHAT? I was about 25,000 miles from home and needed some kind of treatment, probably soon, and probably needed to go to the hospital. My Thai is sadly limited mostly to greetings and niceties, but not enough to explain the intricacies of a complex illness and symptoms.

This is where previous connections, a fantastic dedicated home oncologist, and the wonder of the internet came together. Within about 12 hours, I was able to make contact with my primary oncologist, e-mail colleagues and connections at the University of Minnesota and in Chiang Mai, and decide next steps. After trying as hard as I could to avoid hospitalization, it was apparent that the hospital was the place I needed to be. I was fortunate to be in Thailand, compared to many other countries in the region. Many people come to Bangkok or Chiang Mai from the U.S. for medical care, and many of the staff, including my oncologist in Thailand, trained in the U.S. (the Mayo clinic, in the case of my Thai oncologist).

Thus began my two-week stint at Chiangmai Ram Hospital. I will say from the outset that the care I received was excellent. It was essentially the same care I would have received at Regions Hospital in St. Paul, where I would eventually go for care. I was started on pulse doses (1,000mg) of methylprednisolone. Within two days, my hemoglobin had dropped further to 5.1, and I had to get transfused. Over then next two weeks, I received a total of four transfusions, high doses of steroids, and a dose of IVIG.

My room at Chiangmai Ram Hospital – larger than many at home, and it included a kitchenette, table, and seating area.

I have heard it said that doctors and nurses make lousy patients. I am sure this was true in my case. At the beginning, I was trying to treat myself as a patient. Morning labs would come, I would sit on the edge of the bed waiting for my nurse to bring in the results, and I would plan what hoped would happen that day. Initially after transfusion my hemoglobin stabilized and didn’t drop for about 2 days. I was ecstatic and began to plan my trip home. Turns out this was premature.

Another saving grace of my hospitalization was travel medical/evacuation insurance. I work in a travel clinic doing pre-travel consults as part of my job. Travel insurance is something that I often recommend to anyone who travels, and the University of Minnesota requires that any faculty who travel purchase it. I have never been more thankful for having it. As you can imagine, getting sick while abroad as well as having my family with me was a very stressful experience. I was very thankful for the people at CISI insurance, who diligently checked in with me, covered the cost of my medical care in Thailand, and ultimately arranged my trip home.

After my initial transfusion, steroids, and stabilization, I directed my energies towards showing that I was “fit to fly.” Many people do not know that most airlines will not allow you board their flight unless your hemoglobin is over 9. I suspect there are a lot of fliers out there who fly with a much lower hemoglobin that the airlines never know about. But nobody wants an in-flight emergency, and there has been evidence of hypoxia at altitude (airline cabins are generally pressurized to around 5,000-10,000 feet). To prove that I was fit enough, I would walk around the unit asking to check my pulse and oxygen level. I even discovered an iPhone app that used the camera to check my pulse. Who knows, there is probably even a Bluetooth continuous hemoglobin monitor that I could have had installed and geeked-out about. Had it been affordable and available, I probably would have bought it.

When I started on prednisone for ITP last spring, I had not been prepared for the manic phase upon initially starting it. I remembered it this time, but I was not prepared for the jolt that accompanied 1,000mg of methylprednisolone. I was admitted to the hospital in the evening, which meant my first dose of methylpred started about midnight and ran for a few hours. Not much sleep that night. Or the next night. Or the next one either. But I felt great! I was elated that we were kicking this hemolytic anemia in the ass. A couple of doses of methylpred, then some oral steroids, discharge, and moving on to bigger and better things. Maybe we would even make the beach visit to southern Thailand we had planned. I started planning curriculum work on the global health course I help direct, tried to think about my overall work-life balance, plan vacation activities for my wife and kids while I was hospitalized. At one point, I was even doing push-ups on the floor (got to fourteen) to show that I STILL was not getting tachycardic or dyspneic and could be fit to fly. We began the trip planning to get home, which turned out to be more complex than I had thought.

After about a week, the lack of sleep (and reality) crashed down. Over one night, I could feel myself becoming more dyspneic, especially with getting up to use the bathroom. On my next lab check, my Hgb had dropped from 6.7 to 5.2. I could really feel my shortness of breath even just lying in bed. That night I was transferred to the ICU for IVIG and two more transfusions.

One of the things I had not spent much time thinking about while working on the OTHER side of the hospital bed is how much time there is for sitting around and thinking when you are in the hospital (especially if you are not sleeping). Between boredom, lack of sleep, worry, and the irrationality that accompanied the mega-doses of steroids, I can say that there were times that I was an emotional wreck. I traditionally have not been much of a crier. Objectively, it was easy to feel sorry for myself. I am young and have a chronic cancer (not fair). We already had to cut out our plan for a sabbatical because of my CLL (not fair). We had been planning this work and vacation, and I made it through the work time but got sick right at the start of vacation (bummer). My wife had been doing the primary parenting while I worked with the course, and now I could not relieve her during the last two weeks of our “vacation” (more bad husband points). I was scared – what if this does not turn around and I need true chemotherapy for my CLL sooner? And what does that mean for my working and academic career? There were times when I would break down at the drop of a hat. A nostalgic song on the iPhone, a hug from Maia or the boys, or even the end of the Lion King when Rafiki holds up Simba and Nala’s child over the pride. Who knew that would be such a tearjerker? During the downtime in the hospital, there is a lot of time alone in the room by yourself that you can really delve deep and perseverate on symptoms (“hmmm…could that flank pain be a retroperitoneal hematoma?”), words spoken by doctors or nurses (“see you later…” does that really mean see you later, and if so what time), or worries (“what if…”). Ultimately, none of this actually helps with recovery. It just winds you up.

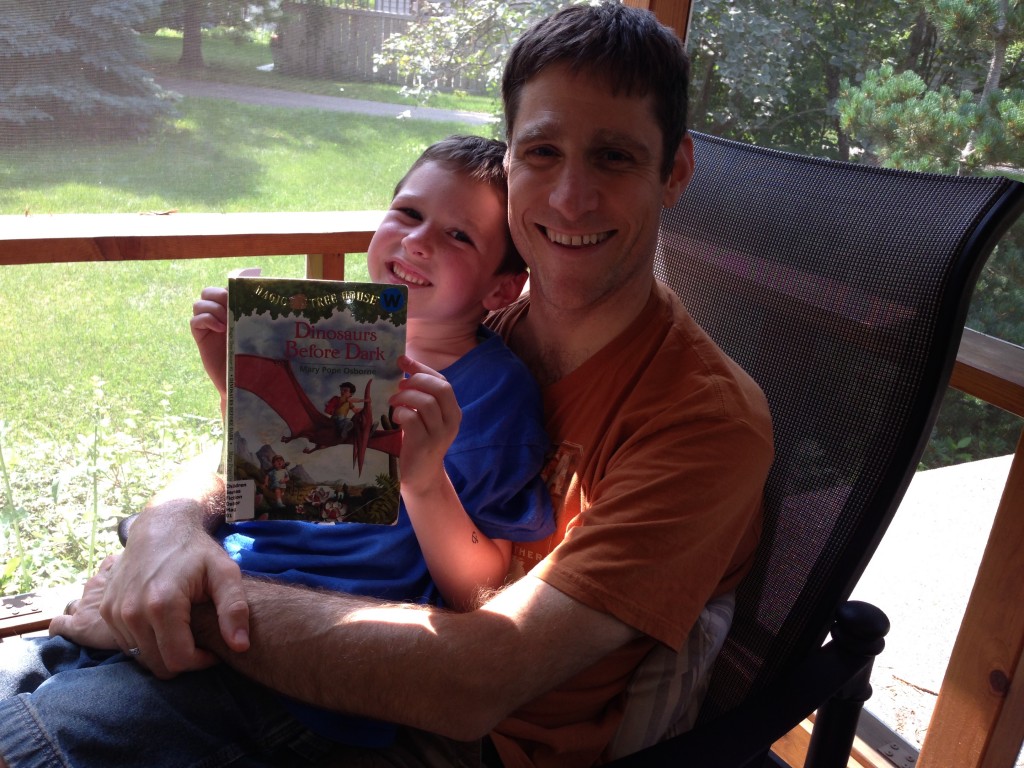

And I missed my family. With the boys being 6 and 9, they could usually hold it together for about 60-90 minutes in the hospital, and that was with iPad available for most of the time. As a family, we had to partition our duties. I focused on my medical care, and Maia continued to assume the primary parent role and kept the boys entertained. While I was sitting in the hospital, they were able to ride elephants, visit temples, see the Golden Triangle, visit Laos, and go shopping in the markets around Chiang Mai. I had been hoping to take them around to all these places myself since I was the one who had been to Chiang Mai before, but it was not to be.

My stellar team of nurses, nursing assistants, and pharmacists at Chiangmai Ram Hospital the day before I left.

Our emotional breakthrough came around day eleven in the hospital. It was that day that I was finally able to step back from the doctor/patient role I had been assuming and focus just on being a patient. I had been through a lot of ups and downs, and I just could not handle the emotional rollercoaster of high highs, and low lows. We made the very tough decision as a family to send Maia and the boys back to the U.S., not knowing what would happen to me or when I would be able to fly home. They flew out the next morning to Bangkok, and then back home to Minnesota. I think that saying goodbye to Maia and the boys was one of the hardest things I have had to do as a husband and father.

The Air Ambulance ride home – never have had my own private jet before. The team was great, but it wasn’t worth the trouble that led up to it!

As it turned out, the rest of the hospitalization was anti-climactic. I am not sure if patients realize it, but the goal in the hospital should be always to be a very boring patient. You hope that everything goes completely by the books. Problem – diagnosis – treatment – stabilization – discharge. That was what the last several days were for me. My hemoglobin began a steady upward trend. 5.2 – 5.8 – 6.5 – 7 – 7.5, etc.

The problem remained of how I would get home. In my case, I did not want to be transfused up to a hemoglobin of 9. I was feeling well enough at 7, and with the ongoing hemolysis it would likely take a lot of transfusions to reach the airline parameters. This was once again where the travel medical evacuation insurance shined. I can not say enough good things about them. CISI organized an air ambulance flight home for me, accompanied with a doctor and nurse and a crash cart (bag) with oxygen as far as Tokyo, then a domestic business class ticket with the doctor sitting right behind me checking vital signs periodically.

My first trip in international business class (with complementary pre-flight ginger ale). Again – it was great, but not worth the trouble. Dr. Sura was in the seat behind me.

I ended up not needing any interventions during the flight, but it still took come convincing on the part of the doctor to show the airline that I was fit to fly. I made it back to MSP with no complications, made it through customs, and met an ambulance that then escorted me to Regions Hospital (“take me to Regions” is one of our slogans, and I was never happier to utter it). From there I was further stabilized, monitored, and later sent home.

So – how did we make it through this situation? I can not pretend that we had it all figured out. We have the benefit of hindsight – we DID make it through. Things went about as well as could be expected, and I think I WAS a fairly boring patient, at least in terms of complications and expected course with a hemolytic anemia. We are all still talking to each other. For us, the love and support of family and friends at home and in Thailand made a huge difference. I had frequent visitors from the Faculty of Medicine at Chiang Mai University, the Faculty of Vetrinary Medicine, and some colleagues from Bangkok even flew up to visit. We had the benefit of local friends who helped show Maia and the boys around, helped us find lodging when we extended our stay, and helped us navigate the basics of daily life around Chiang Mai.

Take Me to Regions Hospital – the view out my window back in St. Paul. Even though I work here I couldn’t score a river view room across the hall.

For me personally, I tried to focus on being present and trying to control the things I could control. I attempted to re-engage with a mindfulness practice, and I appreciated the various options for technology-based entertainment. Thank God for Overdrive, eBooks from my library, e-mail, crappy TV, and movies. Being able to connect from afar with my oncologist, family, and friends made a big difference.

Over the past month, I have been recovering mostly at home. After six weeks, prednisone, and a course of rituximab my hemolysis is stable but still there. My hemoglobin cracked double digits a few weeks ago. I started working just a few half-days in clinic, and next week I am hoping to go back to working on our palliative care service. I will need to work on pacing myself at work, getting good sleep and nutrition, and finding a way to avoid overstretching myself. This will be my biggest challenge. But at least whatever comes next in the journey, it will start from my own bed with my home care team.

Despite all of the ups and down, the most present sentiment after all of this is gratitude. I am grateful that I made it through this hospitalization. I was fortunate that despite the severity of illness, my symptom burden was not too bad. I am very thankful for the excellent care I received from my healthcare team at Chiangmai Ram hospital and later at Regions. I am so thankful for the support of our friends and family who I knew were pulling for me both in Thailand and the U.S. I also have the best oncologist around. And my colleagues have been fantastic. Nobody wants to have to call in for back-up, but their flexibility and support have made this time a lot easier to bear. But I am most thankful for my wife, Maia, who was the rock for our family through this storm. I married up. We celebrated our fourteenth anniversary in the hospital. Here’s to hoping that next year I can at least take her out for a nicer dinner…

You wore a smile in every picture I saw of your travails in Thailand. Meanwhile, I have been whining about the minor bruises and such I suffered from a minor fall off my bicycle. You are a stronger man than I could be, stay that way!

Wow. I have much respect for you, Brett. Get well soon.

What a nail-biter! Your story echoes particularly loud for me, since just two days before I read this on Monday, I met Dr. Matt Dudley at MedicineX at Stanford, where he was an ePatient Scholar. He’s a hospitalist in Anchorage, AK, who gave a MedX ignite talk about his ongoing fight against acute myelogenous leukemia.

I’m the producer of the podcast series for The Hospitalist Magazine. Don’t be surprised when I pop up in your inbox asking for an interview for a Doctor As Patient feature sometime soon …