How often do you hear the following: the average senior utilizes 25% of their lifetime health spend during their last six months of life. Too much.

All that service use in such a concentrated period suggests possibilities. ICUs and inpatient care have great costs. Our acute and post-acute institutions also do not hold up as models of efficient care delivery. Most of them at least. What to do?

I see the above observations as something akin to an emperor with no clothes. Because leaders with checkbooks have a focus on areas that will generate cost reductions, they seek opportunities they can wrap their arms around. The more disadvantaged and disjointed ambulatory practices cause too many headaches. Hospitals then seem like the right place. Hospitalists and inpatient practitioners seem like the right people. The logic goes, with advanced directives and creative thinking, the right docs and facilities can make a dent in utilization.

That is the narrative we currently hold firm. The truth, however, gets us back to our underdressed emperor and the tendency to oversimplify problems. Think care variations unique to geographic regions; that did not turn out so good. The intuitions most of us have about end of life care probably situate in the same silo—and an original, interesting paper bears that out.

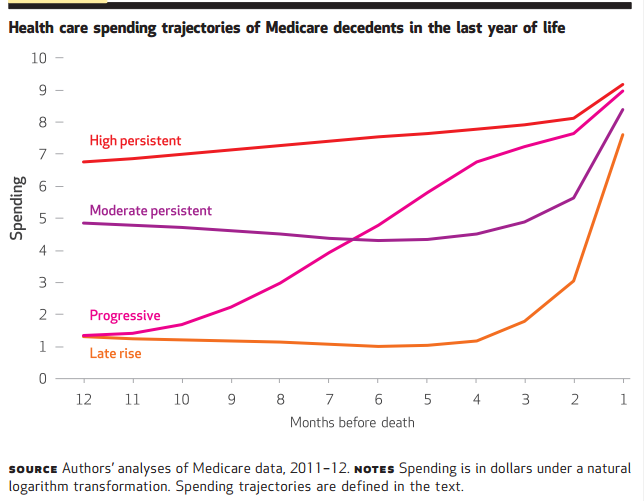

You can reference the article here, but the figure below summarizes the often underappreciated end of life patterns we neglect. What you see is a timeline twelve months before death. Some individuals, by their illness, maintain a high burden of service use most of us would recognize: think ongoing IPF or ALS. But there is a significant number of patients whose courses we would not predict and whose care would fix in outpatient offices, rehab facilities, or even at home with family. By their life course, you could not foretell their prognosis and more to the point, be able to intervene with care plans to mitigate a slide most of us would characterize as burdensome, often futile, and sometimes wasteful. It obliterates the myth of the “last six months,” and how we as inpatient providers could improve our targeting of care. It’s not just those who provide care in acute and subacute facilities, but everyone involved in a patient’s care who engenders responsibility.

Also, as a reminder, even if we could prognosticate, several caveats you should keep in mind:

- Advanced directives are coarse, and they entail dynamic decision-making—what folks want today they don’t want tomorrow. ADs are a partial solution.

- Even with detailed documents, families often cannot translate the wishes of their loved ones. In hindsight, defining “no excessive, burdensome care,” can be more than unwieldy.

- We all think death comes in a predictable manner. Folks never know its “now.” That is only in the movies.

- We only can analyze death post hoc. Defining the denominator prospectively is impossible with today’s tools.

The list could go on, but nothing about end of life care decision making is easy. The findings of the paper just muddy the waters more.

As a bonus, the above gives me a reason to highlight a study I have meant to cite for some time. I found the discussion within it worthwhile.

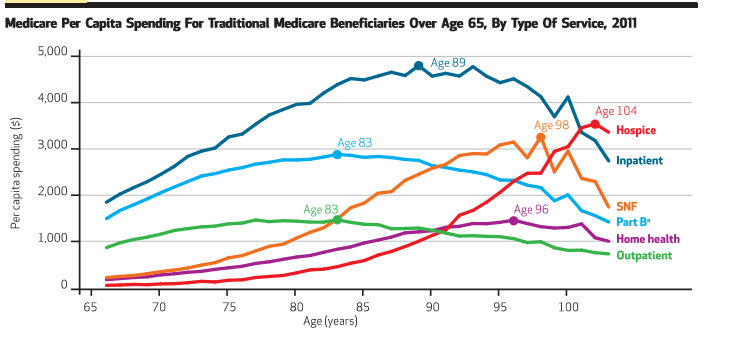

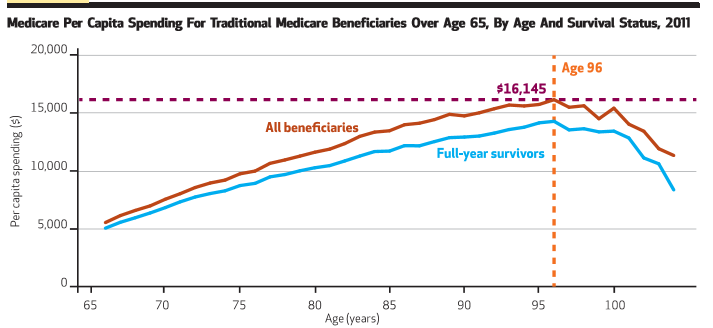

The work concerns spending in the Medicare program across the lifetime scale. Two figures from it I plucked below, and they give the peak dollar utilization across various service lines a beneficiary might experience and also per capita spending across the age spectrum, respectively. The individual spend on the inpatient side tops out at age 89 (top) and the if you are lucky to live to age 96, you will have extracted the greatest value from all those taxes you paid: average per capita spend equals $16K (bottom). It is interesting stuff so have a look.

Also, see HERE. Some people are listening.

Hi Brad,

Thanks for sharing some interesting data about Medicare spending across the spectrum of healthcare, and its relation to end of life decision making. Advance directive serve as a guidance to families in situations where decision making might not be easy. I think that while the inpatient setting seems to be a relatively easily accessible focus for attempts at impacting resource use, it is important to look at it across different settings, with focus on individual patient. Care coordination using mulitidisciplinary teams could possibly be more effective in this regard.

Thanks.

Rupesh.