By reading the headlines recently, practitioners would not know if they saved or tanked the healthcare system. One day disaster looms, the next we have moderated growth and business can continue as usual (and by business, I mean doing the correct things correctly).

A new study, along with some recent data, helps shed some light on the issue.

Out in JAMA Internal Medicine this week, Likosky and colleagues sought to determine MI cost growth in Medicare beneficiaries from 1999 to 2008. While MI’s are not representative of the system at large, for the purposes of the post, I will use the diagnosis as the canary in the healthcare system coalmine.

In their study, the authors adjusted for risk, price and inflation, and looked at intervals of time ranging from the admission, through day 30 and to 365. Although they found a 19.2% decline in the rate of hospitalizations, they noted an overall increase in expenditures per patient by 16.5%. Why?

By looking at the following, you might expect a decrease.

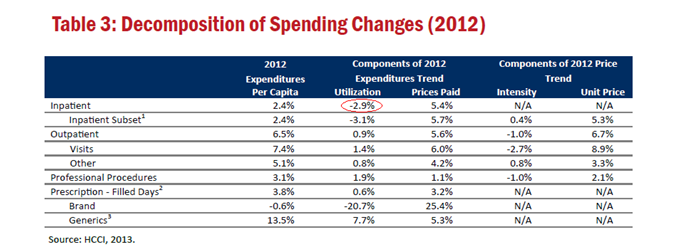

Overall healthcare costs are down (non-Medicare, but similar trend):

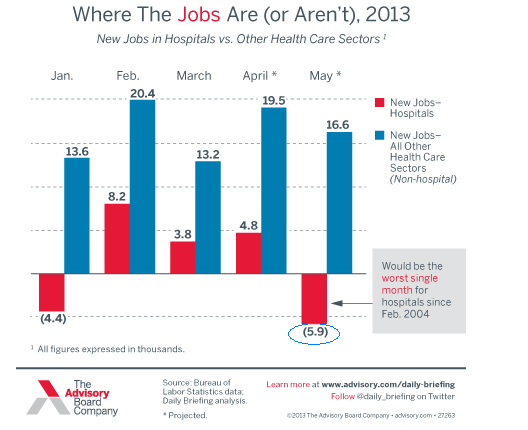

Hospital jobs, breaking a long historical pattern, are down:

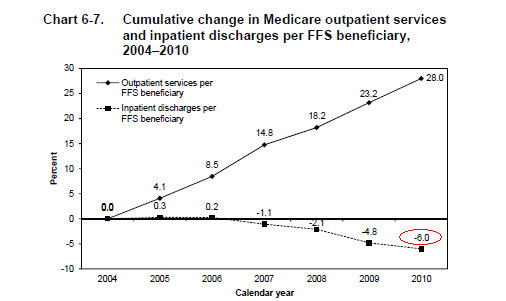

Inpatient utilization is down:

What gives?

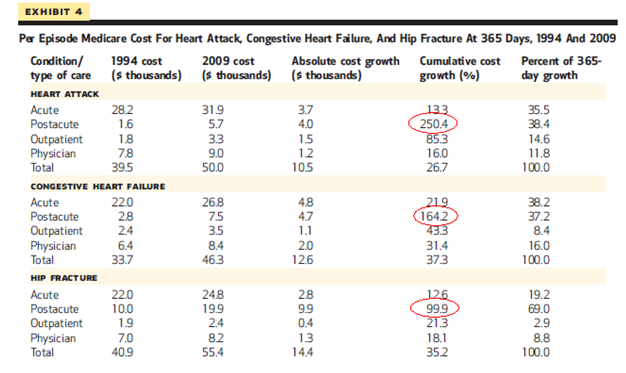

As Ashish Jha refines in his commentary, the problem lies not in the stay itself, but everything we do afterwords. The bulk of the costs come following, not prior to the discharge (74.4% happened 31 to 365 days after the index admission). The rehab, home care, physical therapy, and needed outpatient care all go into the mix.

Yes, we apply more technology and apply some pretty amazing and costly stuff in house, and in doing so, save lives and more efficiently than ever. However, the pocketbook-ectomy after patients leave the hospital walls stem from a narrative we all know well–disjointed care with uncertain value.

The pressure plied on providers working within the hospital, i.e., “get costs down,” has wrought great pressure, especially as we focus on readmissions and hospital throughput. My impression of CMS’s approach however, along with Ashish’s, comes up short. CMS and other payers need to look beyond the inpatient facility and into the business of post-acute care.

While I can cite reasons for the inpatient transformation (critical care, technology, drugs), I cannot clarify fully our system’s performance as it moves into the community. How many physical therapy sessions, health aide hours, rehabilitation days, ambulette rides, and occupational therapy sessions equals too much. Do we attribute it to the woodwork effect and waste as root cause, or have we caught up with overlooked cracks in the system not addressed twenty years ago? Patients and families now get what they require.

Jha is skeptical:

“Although readmission rates in the late period remained stable, the spending per readmission went up—with little evidence that patients benefited. It is debatable whether the use of these additional services improved the quality of life of Medicare beneficiaries—but the study by Likosky et al provides little evidence that it did. It is not debatable, however, that these additional services are expensive not just to Medicare but to the beneficiaries as well. The additional services generate substantial out-of-pocket costs and put patients at risk for iatrogenic events. Absent better evidence about which services are valuable for beneficiaries following early period post-acute care, as well as the specific situations in which they are valuable, it is unclear whether Medicare’s current approach to paying for them is justified.”

I agree to a point, and am not comfortable dismissing improvements in quality of life completely. Relief of family burden and other positive externalities (patients may return to a more productive level of fucntion) may exist and if so, still need elucidation. Regardless, we likely pay a premium for whatever goodness we receive in return. Any betterments will require more study though–we dont have enough data– and changes in payment and system organization must follow.

Additionally, make no mistake about the data above. Other recent evidence of cost growth for postacute care from a recent Health Affairs paper duplicates the findings. At least we know where to aim the slingshot:

UPDATE: This week’s JAMA contains a short commentary on a recent congressionally tasked IOM report concerning similar issues. The committee found the same postacute cost phenomena.

[…] more, that is, than a series of good graphs. For that, I direct you to Bradley Flansbaum’s post, The Rate of MI Hospital Stays Decrease, Yet Total Cost of Care Goes Up? Over at his blog, The Hospital Leader, Brad tells the story beautifully (for those enamored with […]

[…] Posted at The Hospital Leader on […]