Like you, I am focused on care transitions these days. Inpatient providers have gotten closer to mastering the hospital side of things (disease-specific care), but we still have a long way to go on broad-based QI with items such as hand washing, nosocomial infections, and patient communication. Additionally, the patient’s passage back from the wards to the community, either home or into post-acute care, has been under the microscope. The detrimental effects of deconditioning, lack of sleep, the introduction of new medicines, and the catabolic effects of illness puts patients in a tight spot when they no longer have 24/7 supervision and may have to wait a week or more before seeing their provider.

CMS attempted to remedy the above when a few years back they introduced reimbursable transitional care management codes (99495 and 99496):

The payment for transitional care varies with the complexity of the patient needs specified non–face-to-face care coordination services in addition to an office visit following discharge from a hospital, a skilled nursing facility, a rehabilitative facility, or an outpatient facility for an observational stay. For patients with highly complex conditions, the office visit must be within 7 days of an eligible discharge; for patients with moderately complex conditions, the office visit must be within 14 days. In each case, a care team member must also communicate with the beneficiary or caregiver within 2 business days after the eligible discharge. TCM services paid $145 for the supplemental care versus $105 for a routine office visit.

The investigators in the referenced JAMA study above sought to determine whether the codes made any difference. They studied Medicare patient outcomes after day 30: mortality, readmits, and costs of care for a total sample of 18 million encounters. The investigators compared those individuals who had a <14-day post-discharge visit with and without a TCM code attachment as well as folks who had neither (no f/u at all). The author’s adjusted for multiple demographic and clinical variables as well.

Incidentally, the author’s looked at >day 30 only, as any deaths from the day of discharge through the first few days would bias the results aaway from the null. Folks would not have had an opportunity to advantage themselves of the added TCM engagement if they were not alive (immortal time bias).

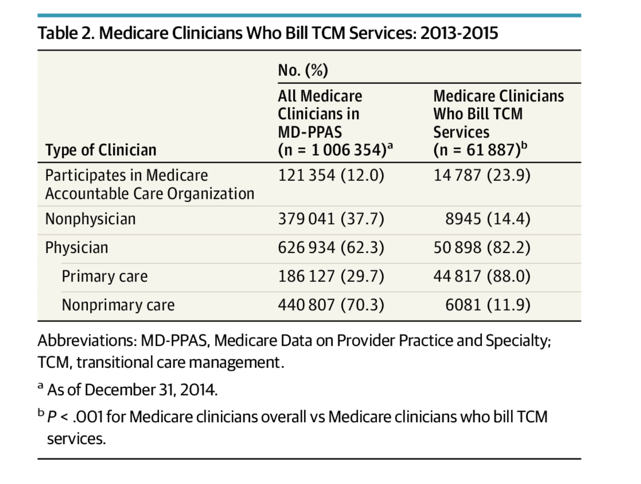

First, uptake of the codes was slight going from 2% to 7% of eligible beneficiaries (FFS parts A, B, D) from 2013-15—and HERE for 2017 use apart from study. The use of them concentrated in a small number of practices, with mostly physicians applying them to a post-hospital visit (vs. SNF, observation status, or LTACH). Not surprisingly, ACOs put them to greater use as a proportion of TCM providers compared to non-appliers.

A quick summary of the findings reveals statistically significant lower cost (~$300 or 10% decrease), lower mortality (~0.5%), and a decreased readmit rate (~0.2%).

What component of the TCM service produces the contrast? It is anyone’s guess, and with the infinite number of studies and various outcomes on care management supplementation using follow up calls, you cannot say if it’s the service itself, the types of patients that engage in it, or the skill of the practices billing for it. In other words, bias.

For the purposes of discussion, let’s say the TCM service has a (+) effect. Then we can conclude a beneficial encounter does not have the kind of uptake we would like to see.

For one, the bump up in reimbursement is peanuts considering an office needs a system in place to know discharges have occurred, employing a staff savvy enough to target these folks for rapid follow up, and then getting the patient in on time to meet the codes clock-based requirements. Not rocket science, but a digression from business as usual flow not worthy of the small ball dollar enhancement.

Well, we got a few choices:

1) Keep the status quo. Oh, well.

2) Sweeten the pot and up the value of the code;(it has been adjusted with time, but only a trifle).

3) Rely on global fees and count on more soup to nuts care.

4) Put hospital systems in place to alert providers—IT or hospitalist driven or both.

5) Follow the lead of Medicare Advantage, i.e., utilize greater oversight and reimburse for non-medical services (coming online now).

The only answer I can offer is #2-5 plus time. The acorn will grow into the oak in the next decade. Until then, it is the muddled dance–no different than implementing simultaneous hospice & palliative care, nixing observation status, fielding telehealth, and perfecting advanced care planning. Also, if CMS wants to ride the economic crack high, I will give them a back of the envelope: figure 4 million transitional care encounters x $125 bump = $500M. There is your short-term fix.

A terrific FAQ here, btw.

Leave A Comment