This recent article in the NYT and the NEJM study precipitating it widened the (malevolent) coverage of the fees paid by patients and insurance companies to out of network physicians. If you are not familiar with the issue, doctors working in hospitals–who may not participate in the plans the hospitals accept–separately bill the insurance companies for higher than average charges. Since there is no upfront negotiated discount, typically found when docs belong to a plan, the insurance company may or may not pay the asking fee. If they do not, the often sky-high balance becomes the patient’s responsibility. From the patient’s point of view, the process makes no sense; if a hospital participates in their plan, so should the docs. Not so. Hospitals do their thing. Professional do theirs.

The problem of balance billing and out of network providers does not reside in one or two states, and the practice touches all manner of hospital-based physicians: radiologists, anesthesiologists, pathologists and in particular, emergency room physicians. In fact, the ER docs have engaged in their own mini-campaign to push back on the negative spotlight focused on them. See their video here.

The finger pointing between insurance companies and professional societies (and patient groups) has worsened and consequently, some states have passed or are moving bills to hold the patient harmless and create a dispute resolution process acceptable to all parties.

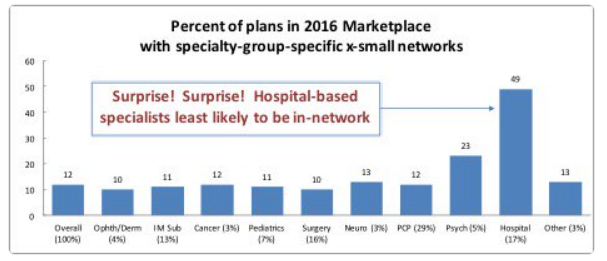

Something I have not been able to nail down, however, concerns hospitalists and how we fit into this problem. Studies like this one lump all hospital-based docs together into a big bucket while also applying vague data definitions—as hospitalists are not specifically mentioned in their hospital group designation:

As I have noted in the past, the lack of detail in capturing a specialty as large as ours, 50,000 providers, lays bare the problems of the work above. We do not have a specialty code.

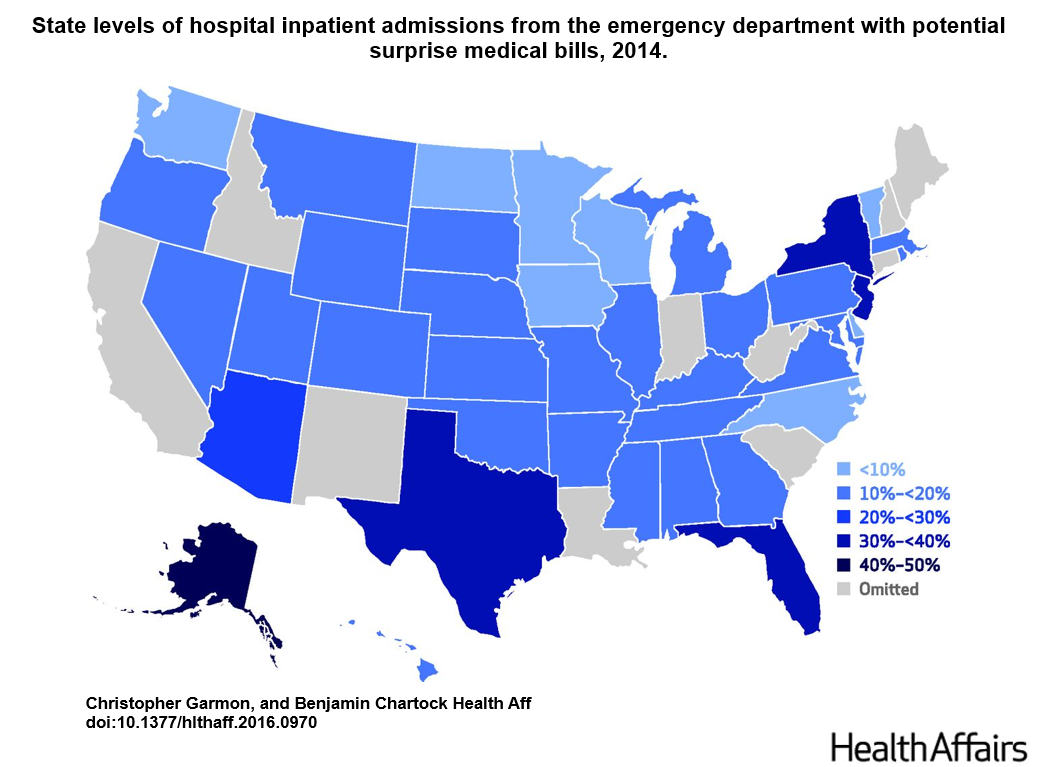

A recent publication from Health Affairs entitled, One In Five Inpatient Emergency Department Cases May Lead To Surprise Bills, gets closer to the question. The investigators looked at hospital inpatient admissions originating in the emergency department and found twenty percent of patients likely received a surprise medical bill. In this study, they defined hospital-based docs as anesthesiologists, ED physicians, radiologists, pathologists, and hospitalists. Given the data arises from a tuned database comprised of commercial payers, the authors may have had the means to finger each discipline with more specificity. Regardless, you can see the national scope of the problem in this figure:http://content.healthaffairs.org/content/suppl/2016/12/14/hlthaff.2016.0970.DC1/2016-0970_Garmon_Appendix.pdf

As helpful as the citation might be in raising potential red flags, though, we do not know the extent of the issue within our ranks. While I am not delving into the propriety of insurers or providers, the blame for hardships can likely be shared by many. I am sure hospitalist groups not employed by hospitals (private practice and contracted corporate entities who disengage from hospital–MCO arrangements) have encountered this difficulty or are, gulp, guilty of it.

So you can see the problem. Again, how can SHM advocate for or attempt to solve an issue we know occurs within our organization but can’t diagnose? An approach employing sign-on letters, model hospital arrangements, and state mediation standards eludes us because we lack the means to delve into the national discourse transpiring right now.

This is an excellent case study on why we need to define our specialty and acquire the ability to distinguish the patients we do touch from the ones we don’t. Without that capacity, we will remain on the sideline–suffering from the malady of paralysis by analysis. Besides, we are the biggest group of hospital-based docs in medicine. You think folks would want to know what we were up to.

Leave A Comment