A good idea, but not quite.

A subject I hope to engage more in depth in the future concerns how career hospitalists age into our specialty. As the healthcare system veers toward greater patient responsiveness, 24/7 access to caregivers will be a priority. As physicians continue to offload their night and weekend work, hospitalists will pick up the slack. It’s happening as we speak.

No one likes nights, weekends and holidays. Physicians working those shifts over a lifetime like them even less. Yet we hear little about the drag these uneven schedules introduce as our careers progress. Our deferral of the day of reckoning stems from an influx of newbies into the specialty as well as the young age of the average hospitalist, approximately forty.

Many folks I speak with who consult within hospital medicine discuss burnout as a major road motif. They hear from docs working ten plus years in the the field and the message unifies around a theme of prostration or uncertainty.

Will it take salary, a job description change, or less time working to attenuate the impact of the off-hour grind?

A recent BMJ post caught my eye addressing the same. An NHS critique:

[…] Mann said that the college’s plea focused on the need for there to be a “fair equality of leisure and family time” for doctors working in different settings. “What we’re simply arguing is that, if you give up lots of nights, evenings, and weekends—which is par for the course for working in any acute specialty, whether that is interventional radiology, acute pediatrics, or emergency medicine—what you want is not more money. You want to be able to repay the lost time with your family, your friends, or your fishing rod that you have given up,” he said.

He added, “I’ve worked part, or all, of the last four weekends. It’s no good people saying to me, ‘We want you to work another weekend and therefore miss your daughter’s first netball match, or your wife’s dance show, or whatever it is.’ There is no amount of money that will buy me enough team points to compensate for not being at those things.”

[,,,] He said that it was not enough to be given a week day off to compensate for working a day at the weekend, because it was unlikely that doctors would be able to spend that week day off with family or friends. “What we’re saying is you simply link the proportion of out-of-hours work you do to the amount of annual leave you are entitled to get,” he said. “That way I can say to my daughter, “Yes, I spend far fewer Saturdays with you [than other parents spend with their children]. But, as a family, you spend the same number of days per year together at times of our choosing just like those other families do.”

The author conveys what many of us already know, mainly, hours worked do not equal hours toiled. Patients want night and day access and payers’ better outcomes. But the costs to make the change happen may require a scale up in pay with more FTEs. Ignore those facts, and an attitude of nights and weekends be damned will blight the “senior” hospital-based workforce. Over time, docs just might walk.

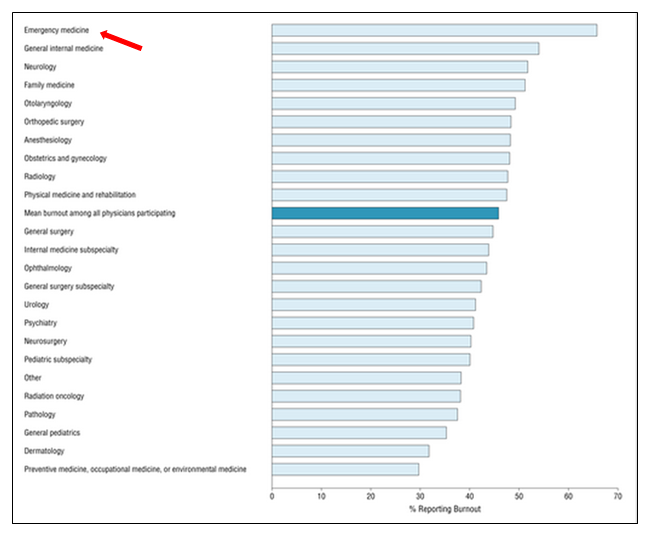

Also, if you think emergency medicine has got it figured out–a kindred specialty we compare ourselves to–not quite. They burn out at a much higher rate than other disciplines:

Can we run our healthcare system like Amazon and Zappos, where differentiating between 3AM and 3PM knows no bounds, without reexamining compensation, i.e., our salary, QOL, and professional satisfaction? Unlikely.

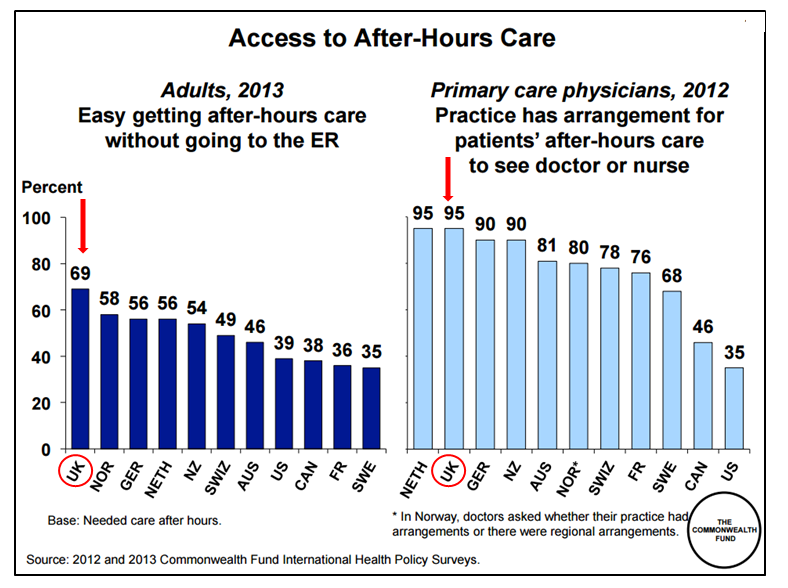

What of international health systems, often compared and embraced over ours for their friendly approach and focus on patient needs? Have they threaded the needle and achieved peak cowbell? Once again, note the UK below:

On one hand we have a responsive NHS leading the pack in after hours access, but on the other, as illustrated in the passages above, an unhappy brood whose charge it is to produce those results. Maybe not such a sustainable endeavor after all.

I agree with creating a better system. Who doesnt. However, the foundation of success requires not just blithely looking overseas and conceiting all is hunky dory; assuming the hospital models of care we utilize now work over the the long haul; and not sampling folks who have been doing this long enough to know after 10-20 years, they may desire a change in career tack.

Not everyone wants to be, nor does the system have room for, twenty thousand ex-hospitalist VPMAs, CMOs, CEOs, and quality officers. Full-time work that comes with less nights and weekends, for less pay, has merit as one option–but the practice wont gain traction without a more factual and authoritative inquiry into our field.

For example, ask a group of 35 versus 45-year-old practitioners, “can you envision working your current schedule in twenty years,” and you will obtain different responses. The upbeat replies we have come to expect in our surveys have more to do with demographics from the former group, rather than the evolving presence of the latter.

Again, I will readdress this issue in the future. In the meantime, I look forward to an SHM initiative concerning hospitalist job satisfaction launching at HM15. Answers might be forthcoming.

Brad: This topic is worthy of a discussion at HM16. You should think about would be most productive — a presentation, a panel discussion, a workshop, . and reach out to the Planning Committee.

Yes, SHM will be launching Hospitalist Engagement Survey service at HM15 and the Board will be subsidizing participation for one year. We believe it can become a valuable management tool for hospitalist leaders. More to come…

JOE

Great post as usual Brad. the number of folks hoping to achieve balance by growing into non-clinical administrative roles smells greater than the demand. What is plan B? I think CCM and ED have very similar issues but have fewer options as they are more terminally differentiated, while it is a little bit easier for hospitalists to jump ship. I think one path to focus on may be limiting 12hr shifts so that folks can at least get home for dinner or a kids soccer practice during the week.