Few media flaps have left me as disappointed in us as a country as the vortex we allowed ourselves to be swept into around the “death panel” debate in 2009. Initially I watched in stunned disbelief, later in anger and frustration as a logical and patient-centered proposal was slandered to the point that it was taken out of the Affordable Care Act, never to resurface until now.

There has been recognition for years that we are failing our patients at the end of their lives – a most vulnerable time – delivering care that is not aligned with patients’ values, puts them through needless suffering, and, by the way, is super expensive. Thankfully, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Service (CMS) is once again considering reimbursing physicians for these voluntary conversations between patients and providers.

In our health care system, care can end up incredibly fragmented. The sicker the patient, the more providers involved in their care. Primary care providers, outpatient specialists, hospitalists, surgeons, inpatient specialists – the team grows quickly and dramatically. Each of us wants the best for our patients, but too often the big picture is lost in our myopic view of “our area,” and too often our patients are lost on a treadmill of continued tests, treatments, therapies that at best do not get patients where they want to be, and at worse may shorten both the length AND quality of their life.

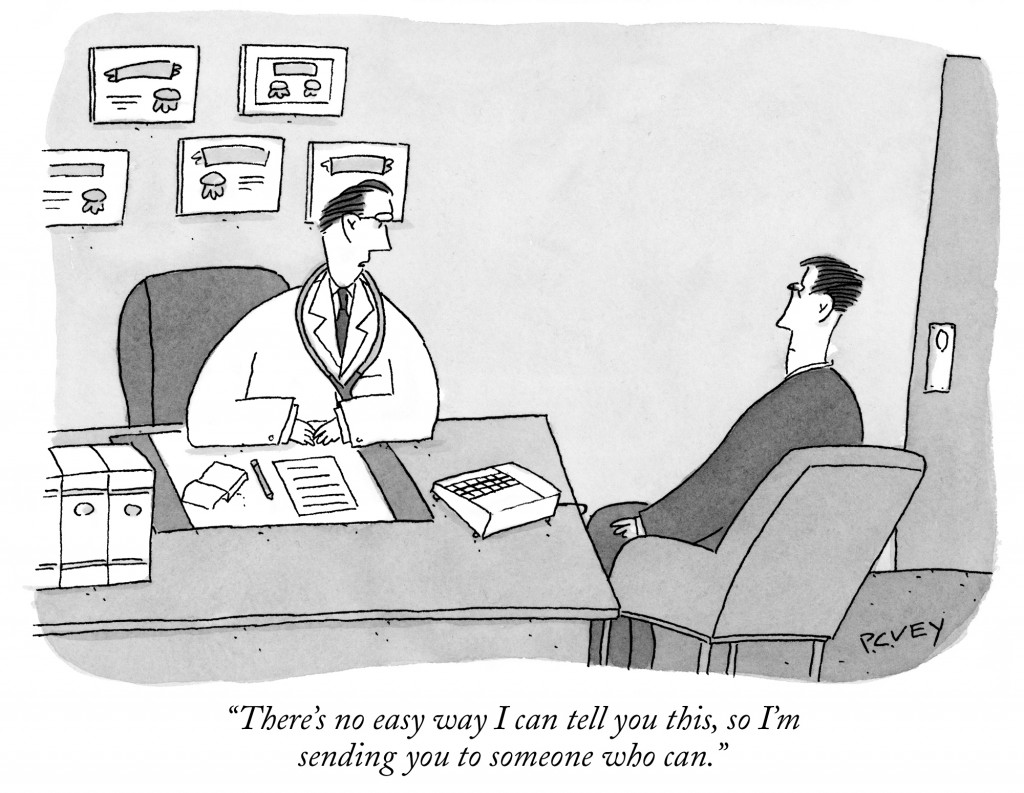

Why do we allow this trifecta of worst care, worst experience, and highest cost to happen? Not out of malice or an attempt to pad our pockets – in fact, many doctors and nurses experience emotional distress and burnout delivering this care. Much of the time, we slog on because none of us has simply spoken to our patients about their goals and priorities at the end of life. Why not? We want to keep hope alive for our patients and their families, to remain positive, and to avoid letting them down. Sometimes we avoid “the talk” because we feel either that it is not our job, or we are uncomfortable having these conversations ourselves.

Friends and colleagues have asked the question, “Whose responsibility is it to talk to patients about death?” My answer is simple: It’s mine. And yours. And anyone else who is involved with the care of a patient with an illness that may limit their length or quality of life. More importantly, we should all be communicating across specialties and across the continuum of care. I’m not expecting the neurosurgeon to spend an hour reviewing what makes life worth living for every patient they are asked to see to discuss a procedure. But we already have a culture of discussing “risks and benefits” of a procedure. I would like to see us progress to discussing risks, benefits, and BURDENS of a procedure. We may think of it when discussing chemotherapy side-effects, or recovery after spine surgery.

But what about the burden of continued lab testing – being woken up at 5am in the hospital to be stuck once (twice? thrice?) for daily labs? Hospitalization itself can be a burden just by its nature, alienating our patients from their friends, family, or their comfort zone. Our patients do better when they know what to expect, how it will help them, and what options they have. And sometimes the best option is choosing a less aggressive course, handling more symptoms and decompensations at home, and even entering hospice.

So why is it a big deal that Medicare has proposed new diagnosis codes to allow reimbursement of physicians for counseling around advance care planning? In a word: time. As a hospitalist and palliative care physician, I am not reimbursed by the procedure. We still have a system where physicians are paid for what they DO, not for what they DON’T do. As a hospitalist I am not paid to cut, poke, or read imaging studies. My reimbursement, like many colleagues in primary care, comes from either the time or complexity of the thinking and counseling that I do with patients. I have no financial incentive to talk a patient out of a procedure. In fact, you could argue that the opposite is true.

Many people are shocked to learn that if they make an appointment with their primary doctor to discuss goals of care, advance care planning, or end of life care, their doc may not be paid for the visit. For insurance companies to pay for thinking and counseling, there needs to be a diagnosis that they will reimburse. Sarah Palin and her ilk managed to convince Americans that simply reimbursing for this conversation would lead to “death panels” out to limit care for chronically ill or dying patients.

So how might the change actually affect our patients? Will I be trading in my white coat for a black cloak and scythe? Perhaps I will change my standard introduction to, “Hello – I’m Dr. Hendel-Paterson, and I’m here to limit your care and usher you towards the light…”

No – none of these things will happen. BUT a reimbursable diagnosis means that it makes it easier to justify time spent in the hospital discussing patients’ priorities and goals of care. Similarly, it means that patients can make appointments with their primary care providers, who know them best, to discuss overall goals of care and advance care planning.

These changes also mean that all of us who care for patients need to up our game. We cannot punt all the conversations around goals of care to palliative care physicians. Quite simply, there are not enough palliative care specialists. Each of us, no matter the specialty, should be prepared to discuss risks, benefits, and particularly burdens of our treatments in clear and straightforward language. No hiding behind jargon or speaking in statistics.

In most cases, subspecialty training in palliative care is not necessary to have these conversations. If you are a provider uncomfortable addressing goals of care, correct that deficiency. There are ample opportunities for in person or online training in communication. Vitaltalk.org and Honoring Choices are good free resources. There are also online trainings available for providers working across language or cultural barriers with their patients.

Patients, families and friends are not off the hook either. No fair sticking our heads in the sand to avoid touchy or uncomfortable topics. We all must take an active role in our health. We should demand clear answers from our healthcare teams. Families and friends of patients who are elderly or have a chronic disease should welcome conversations around goals of care and expect them from our care teams. We should think about what is important to us and what makes life worth living. Having ready answers to these questions can help guide our care teams and help all of us make better decisions, no matter what side of the bed we are on.

Thank you for this!

Well articulated truths on end of life questions and discussions. It is a travesty that “death panel” discussion was left out of the ACA. Thank you for bringing it to the fore again.