Are American workers becoming happier with less? An interesting article in last Friday’s Wall Street Journal reported on the findings of a recent survey of U.S. workers by the Conference Board, a research organization. Although the survey wasn’t specific to healthcare, much less hospitalists, I see some parallels that might cause many of us to stop and think more carefully about what we expect from our work.

The Conference Board’s findings highlight how American workers’ employment relationships are evolving and how that is impacting what Americans think of as a “good” job. The biggest shift has come in the nature of the implied compact between workers and their employers; unlike a generation or two ago, U.S. workers no longer expect to receive a generous benefits and lifelong employment in exchange for hard work and loyalty. In fact, I suspect many younger workers today would face the prospect of lifelong employment with a single company with distaste, if not outright horror.

American workers today tend to have less job security and fewer employer-paid benefits than they did in previous generations. A companion graphic in Saturday’s WSJ reported that while in 1973 only 6% of Americans said they worked too many hours and 7% said they had trouble completing their work in the time allotted, by 2016 26% said they often worked more than 48 hours a week and half said they work during their free time at least periodically. Two-thirds of Americans now say they need to spend at least half of their day working at high speeds or meeting tight deadlines.

Yet despite these trends, the Conference Board found that overall, U.S. workers are more satisfied with their jobs than they have been in the past. The WSJ article posits that workers are happier at work because they have adjusted to lower expectations of the employer-employee relationship. In addition, workers have more flexibility today to change jobs or companies to find the right fit  or pursue advancement, and often have more influence over when, where, and how they do their jobs than ever before. Many are working as temps or independent contractors, or in similar “contingent” arrangements. Finally, more employers are offering a wider array of tools to aid with work-life balance, such as paid medical and family leave.

or pursue advancement, and often have more influence over when, where, and how they do their jobs than ever before. Many are working as temps or independent contractors, or in similar “contingent” arrangements. Finally, more employers are offering a wider array of tools to aid with work-life balance, such as paid medical and family leave.

So what does all this have to do with hospitalists?

Well, first of all, you are in good company. Surveys of hospitalist engagement and burnout suggest that many of you, too, are working excessive hours, feeling pressure to complete your work in the time allotted, and working at uncomfortably high speeds.

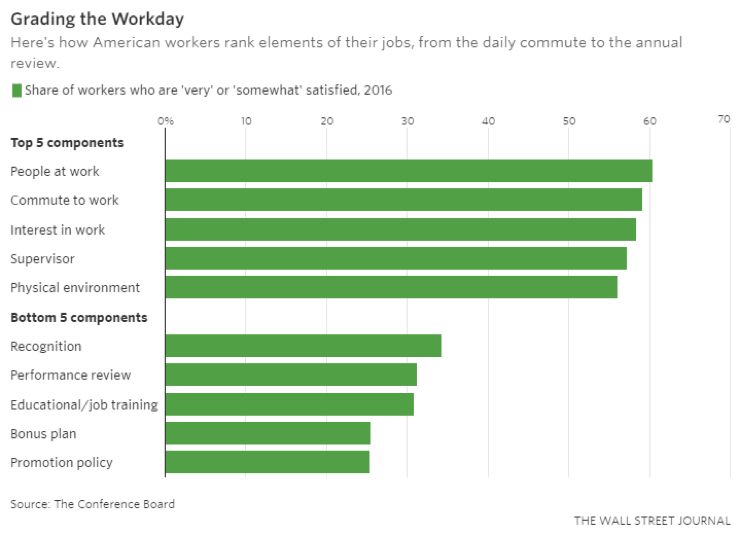

And as is the case for U.S. workers (see graphic), many hospitalists tell me that the most valuable things about their job are their emotional connections with their colleagues and their interest in taking excellent care of patients. They almost universally express concerns about things like inadequate recognition, not getting constructive feedback about how they are performing, and compensation issues. They all know that their employers are trying to increase productivity by doing more with fewer resources.

Most hospitalists have the privilege of a written employment agreement spelling out the technical terms of their employment, something most U.S. workers lack. But I wonder if the presence of written employment agreements has allowed many hospitalists to ignore thoughtful consideration of the implied compact between them and their employer – that is, what can you and your employer each expect to give and receive in order to ensure a mutually satisfying relationship? (I almost said a long-lasting relationship, but for many hospitalists, as for other U.S. workers, “long-lasting” isn’t necessarily what you are looking for.) I wonder if hospitalists, too, may need to adjust to lower expectations of that relationship over time. This is an incredibly important thought exercise for any employee to undertake, and something that is perhaps worth discussing honestly with your employer.

In my view, this thought exercise and some of its outcomes might include:

- Making sure we’ve adopted a reasonable set of expectations that line up well with what our employer is prepared to provide.

- Leveraging those things we like about our current work situation, whether that’s the people we work with, our interests in the work we do, having a strong supportive leader, or a great physical environment to work in, to foster greater job satisfaction.

- Proactively addressing those aspects of our job that are dissatisfiers, such as inadequate recognition or feedback, unsatisfactory compensation plans, or lack of promotion or job enrichment opportunities, with the goal of either changing them to positives or neutralizing their negative impact on our happiness at work.

- Recognizing that these days job security is tenuous across all industries, and although healthcare has traditionally been somewhat immune to economic ups and downs the challenges facing healthcare today are forcing a leaner, more efficient approach that could well mean layoffs and hiring freezes in our organizations – even for physicians and NP/PAs. It would be wise for every worker to make some preparations for this eventuality.

Yes, our employers have a responsibility to provide us with the foundation for a satisfactory work life, consistent with the implied compact. But I would argue that in the end, creating a satisfying work life is just as much our own personal responsibility as it is our employer’s; maybe more.

Leave A Comment