I have always had a bugaboo with mortality rates. It is a clunky standard.

We need death measures to serve as precise tools for quality improvement and hospital performance. If a hospital has a standardized mortality rate of 3%, you can assume only a small percentage of individuals suffered their fate due to medical error. People have cancer. People have end-stage organ failure. People die in hospitals. It’s a fact of life, and we cannot prevent the inevitable. Can a metric give us the nuance we require then?

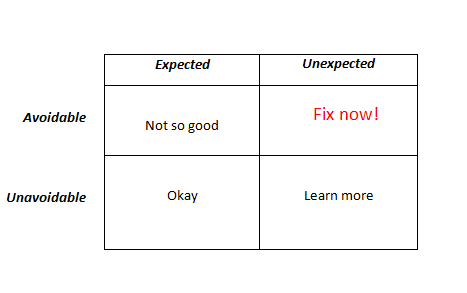

Don’t think of the SMR as a collective sum of how a hospital performs; see it as something similar to what I illustrate in the death table below:

It’s the red box we really want to know more about. But getting avoidable mortality figures can be a chore and a laborious one at that. So, we fall back on the SMR.

The next question then would be can the SMR serve as a reliable proxy measure for the cell in the right, upper corner? Glad you asked.

Out in the BMJ, a new study entitled, Avoidability of hospital deaths and association with hospital-wide mortality ratios: retrospective case record review and regression analysis. The investigators sampled one-hundred cases from each of thirty-four NHS trusts–all with higher than average mortality rates. Independent reviewers evaluated charts to determine avoidability of death (of note, the inter-rater reliability was only moderate [K=0.45]), and searched for an association.

The editorialist sums up the findings:

Firstly, the proportion of hospital deaths judged by a panel of experts to be potentially avoidable was just 3.6%. Secondly, the association between standardised mortality rates and avoidable deaths was, unsurprisingly, non-significant within wide confidence intervals (regression coefficient 0.3, 95% confidence interval -0.2 to 0.7). The signal of avoidable death, it seems, is lost in the din of unavoidable noise. The research team concluded that the association was too weak for overall mortality rates to be an effective monitoring tool.

[…] Given that 97% of patients survive their stay in hospital, this study implies that the proportion of admissions resulting in an avoidable death is around a 10th of 1%. Even the most accurate indicator of avoidable death would barely scratch the surface of suboptimal care.

Might a larger sampling of patients yield more significant findings? Does inter-relater reliability weaken the conclusions? Could we apply the SMR in a different way with other adjustments? Yes to all. Nevertheless, to administrators or the uninformed, using the SMR is like a carnival mirror: things appear larger than they are. Keep this study in mind.

Leave A Comment