“You can observe a lot by just watching.”

-Yogi Berra

“You see, but you do not observe.”

– Sherlock Holmes, A Scandal In Bohemia. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

I walked into the patient’s room day after day and heard the same line. “Sorry, Doc…not ready to get home. My breathing is still bad.” He was sitting up, resting on the bedside table, looking tiny in the expansive, sterile hospital room. This small man with advanced COPD came in six days earlier with an acute exacerbation. The team rounded on him daily. We filled up his room, piling on the windowsill, filing around his bed. His vital signs improved quickly, and by day three, his numbers were great and his lungs opened up. He barely made it through each syllable on day one; almost a week later he was sounding out sentences, making his way to paragraphs.

“It seems you are doing well today, I think you are ready to go home.”

“One more day, Doc. Still have no breath. I’ll be better tomorrow.”

That’s the fourth day in a row I heard that. I have to trust him, he must still feel short of breath, but I felt we were missing something.

I walked back in time this summer while in Italy. It was a trip to the epicenter of Western culture and science and of medicine’s soul – it took my breath away. One of our stops was the University of Padua, which was founded in 1222 and is one of the oldest continuous institutions of higher learning in the world. Many greats of medicine and science strode the halls. Medicine giants such as Morgagni, the father of anatomical pathology, Fallopio, of the Fallopian tubes, Fabrizio, who discovered valves in the veins, and scientific geniuses such as Copernicus. We walked into the anatomy theater in Padua, where I could still smell the faint odor of dissections, picture the students fainting in the narrow stands, and hear the sonorous lecturer bellow up the six-tiered wooden structure.

The art of empiricism had been lost for over a century. Galen, born in the 2nd century AD, took Hippocratic medicine to the next level. He wrote texts of anatomy and medicine that were followed dogmatically for centuries. The material for his anatomy writings were acquired from detailed observations of animal dissections or gladiator injuries. Yet, his art of observation and the testing of theories were lost. What remained were his texts, and Galen’s word was gospel.

Early in the 16th century Vesalius, the famous anatomist, studied and taught at the University of Padua. A keen observer, he was one of the first anatomists to dissect, instead of simply reading the texts. He had an epiphany while dissecting bodies at Padua, as he found numerous mistakes in the Galen texts. Galen was the word and taken as truth for over a thousand years. Vesalius sublimated art and science in his text the Fabrica, and made the first dents in Galenic medicine. He realized that Galen’s works were filled with notes from animal dissections, butGalen never dissected a human! Vesalius, from constant observation, with his own eyes, found what no one saw before.

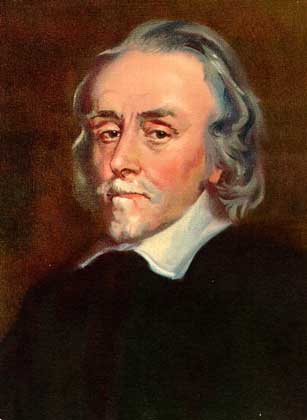

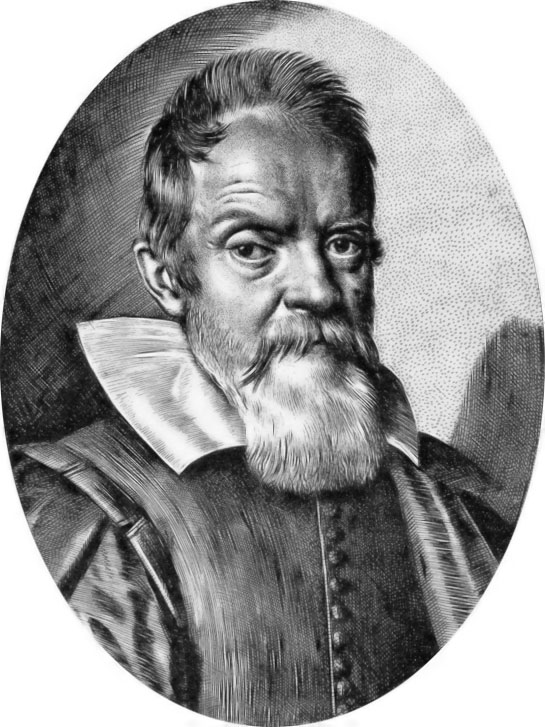

In the late 16th/early 17th century, two men altered the course of medicine and science attended Padua as well. Harvey and Galileo changed the world by seeing for oneself, believing in those series of observations, and standing up for those insights. These fathers of modern science jump started the period of the enlightenment.

Harvey became a Padua anatomy student, graduating in 1602. He uncovered the movement of blood in the body: the lesser and greater circulation. Prior to Harvey, the blood was thought to be made in the liver, travel to the right side of the heart, pass through pores into the left side of the heart, where blood was warmed by innate heat, infused with the pneuma breathed in, and circulated through the body from the contraction of the arteries. For 1300 years that was the belief. Harvey’s empirical studies, observations with his own eyes, and larger cracks in Galenic medicine were uncovered. Textbook medicine was taking a hit, and opened the door for more observations that would transform medicine and the understanding of the human body.

Before Harvey, Galileo graced the halls of Padua, arriving in 1592. His lectern stands in the entrance to the grand hall. I touched it (don’t tell anyone), and felt the earth move. Galileo, who improved the telescope so he could unlock the mysteries of the heavens, was the first to see sun spots, the phases of Venus, the moons of Jupiter, and most famously stood by the Copernican notion that the sun is the center of the universe. By turning the universe inside out, he turned the religious world upside down. Harvey cast aside Galen, Galileo cast aside religious dogma.

They used their own eyes, they challenged doctrine, they unraveled the secrets of the heavens above, and the body on earth. The movement of the planets, the movements of the circulation. Our world in both microcosm and macrocosm changed forever.

Surrounded by this history made me shrink under these giants. Yet, I wanted to inhale their legacy, and stand tall knowing I am, we are, a part of this lineage, proud to be a physician and a scientist. That legacy is powerful, carrying medicine out of the darkness, into the great beauty we are capable of today.

I walked back into his room. He had fallen asleep, and appeared to be breathing comfortably. I wondered why he wasn’t ready to go home. I looked around his room and I saw no one, saw nothing – no balloons, no cards and no visitors. Nothing. He didn’t want to go home, because he was alone -really alone. When he woke up, we talked.

The powers of observation are essential for physicians, and for many a lost art. Centuries of medicine with little technology required the eyes, ears, taste, smell, and touch to be the only way for diagnosis. Observation. To really observe, you must believe in your own eyes. In this case, I saw nothing, but it meant everything.

The ghosts of our ancients filled the ancient anatomy theater of Padua. I inhaled the pneuma of the giants, and came away short of breath. I am reminded to change perspective, to observe, to see for oneself, and that can change the world. Or at least the world of the person in front of me.

Imagine how great medicine, this world would be if they all practiced like Dr. Messler!

Thanks, Becca. You are too kind. (Now where do I send the 20 bucks?)

Great post, Jordan! I was expecting some amazing zebra-catch using the observational powers of the ancients. Instead, you showed us that medicine goes beyond just “fixing” the clinical problem.

Thanks, Burke! So much to say about the power of observation. I went with the simpler diagnosis, the day to day one that we might overlook. Love the zebras one, too. Maybe for future post? Those subtle neuro findings missed for years, the slow turn of the skin color signifying Addison’s that’s picked up by the 20th doctor. Many good cases out there.

Wow, I am seeing a book tour in your future. Hey, being that I graduated from Galen College of Nursing should I be concerned?..Lol Excellent work…Love it.