Think about how many times per week you pull out your medical calculator to plug and play a Wells or CHADS-VASc score. Twice? Three times? Now think about how many times you get pestered about readmissions–be it through case managers, hospital leaders, or through your paycheck. Probably daily.

You can use an app every day and think it’s useful. But it’s the regs and invisible stuff that trumps what you got. That’s my “hand.”

I have written in the past about high impact readmission publications. They may seem far removed from what you do in your everyday lives. Maybe so. But sometimes the audience for these articles are not frontline clinicians–even though their ability to transform your practice life may be more potent than what you would absorb and use from a familiar journal.

Many of us have been carping for years about the post-discharge responsibility period for hospitals as it relates to return trips. Currently, the feds say thirty. But why thirty? Why not twenty-seven or fourteen?

I will tell you why. Because it’s an even number and it rolls off the tongue–no evidence required. Just like someone picked SBP targets of 140, 160, and 180 for hypertension. Again, show me the evidence.

I like this analogy:

However, recent research has raised serious doubts about some of the assumptions that underlie the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program.

First, we now know that readmissions are very hard to predict based on current approaches. The methods used to predict if a patient will be readmitted are only modestly more accurate than a coin toss. To illustrate this problem, consider a hospital that has ten sick patients who leave with a 50% risk of returning to the hospital by the 30th day. While a coin flip would predict five of the ten patients’ outcomes correctly, the current approach gets six outcomes right. Factors related to a patient’s home situation, social and economic circumstances, and community are now known to be important predictors of readmissions (but are ignored by CMS).

Well, when laws pass stating thirty is the new black, you better find nifty ways to convince influential people in DC to modify them. Tons of papers get released demonstrating why ERs readmit patients and what we can or cannot do to prevent them–but for their lack of rigor, they are of little consequence (despite being interesting). Although once in a while, a real game changer gets published you know will land on the desks of those who call the plays. This is one, and I vow folks of a certain ilk will be reading it. The title tips my hand: Rethinking Thirty-Day Hospital Readmissions: Shorter Intervals Might Be Better Indicators of Quality of Care.

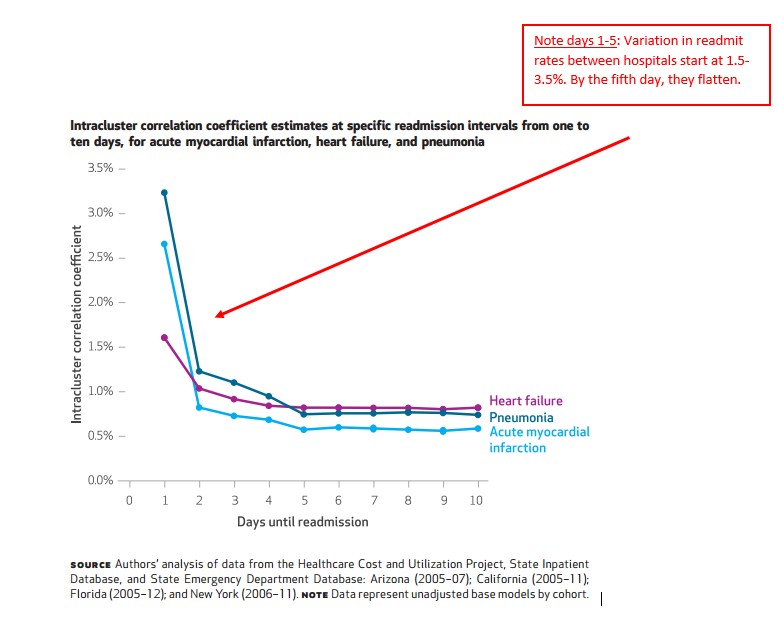

The investigators looked at readmit rates, days one through thirty, for MI, CHF, and PNA. Using models to tease out hospital versus external causes for any variability, they were then able to see the point in time hospitals were “less” accountable for why patients unexpectedly returned to the hospital (assuming that time existed).

Let us say at day seven for PNA, readmit rates ranged from 15-18%, but at day twenty the gap fell to 12-13%. You might conclude the delta of three percent earlier in the stay has more to do with hospitals and the level of 12 or so percent several weeks out has more to do with other factors–because of the narrower range, a consistent floor, and similar all facility performance.

Have a look at the key figure:

The author’s take:

Thirty-day risk-standardized, all-cause, unplanned readmission rates have become widely used to measure hospitals’ performance for public reporting and to impose financial penalties on facilities with excess readmissions,2 despite little evidence that these rates reflect aspects of care that are under hospitals’ direct or indirect control. We found that the hospital quality signal, or hospital-level effect, is strongest within the first seven days after discharge. Factors outside the hospital’s control (community or household characteristics) might have a relatively large effect on readmission risk at longer intervals and reflect the cumulative quality of health care provided to patients.

If the goal of current public policy is to encourage hospitals to assume responsibility for postdischarge adherence and primary care follow-up, then penalties assessed for readmissions within thirty days or longer periods might align appropriately. However, if the goal is empowering patients and families to make health care choices informed by true differences in hospital performance, then a readmission interval of seven days or fewer might be more accurate and equitable.

We link early readmissions post discharge to factors related to hospital performance, i.e., quality. It stands to reason if a hospital has performed short of ideal and a care deficit follows, the variation may be facility dependent and stems from a hospital side miscue. However, if you wish to hold the same hospitals responsible for care beyond the two-week mark, you no longer invoke an element of quality but one of accountability. And if you want to make hospitals accountable for tasks outside of their usual charge (they don’t control patient’s copays to get drugs for example), then payers need to resource them appropriately and find a better measure to assess them.

Once more, this is the kind of paper that gets eyes. When the right somebody sees it, momentum for change accelerates. In turn, the policy shift that ensues will have a lot more impact on your daily grind than a prediction rule or nomogram you bust out on odd Wednesdays every other month.

You have ceded control to a routine you see as normal operating procedure. But you also have not recognized how you have adjusted your practice around a faulty policy layered on weak evidence. Only you have–and you should view it as the cognitive diversion it is. When the fix arrives, hindsight rules and will you realize the misguided grip those same protocols had on time you would have spent on more fulfilling pursuits.

Leave A Comment