If you wish to avert your eyes and palate to the customs of the Brits, fine. Don’t eat fries with vinegar. However, as comparisons go to UK healthcare, you will serve yourself well by absorbing some if not many lessons the NHS has to offer. Hospitals may differ country to country. Regardless, lower weekend staffing ratios and the proclivity of the sickest folks to wait until the last minute to present to the emergency room, often on Saturday or Sunday, do not differ. Most acute care facilities do not operate at full staff 24/7. Most people hate hospitals. Among many commonalities, Americans and British share as much in those attributes.

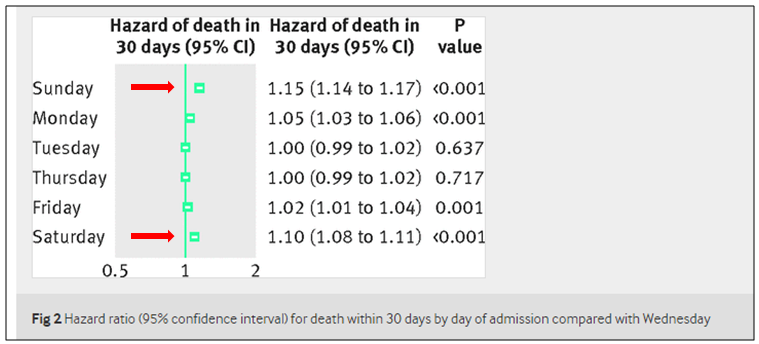

With that in mind, the BMJ just released a reexamination of NHS 2009-10 data comparing hospital mortality rates on patients admitted on weekdays versus weekends. The 2013-14 treatment, with greater refinement in methods, replicates earlier findings. Freemantle and colleagues find an increased risk of death of 10% for admissions on a Saturday and 15% for admissions on a Sunday compared with patients admitted on a Wednesday. They adjusted for case mix, age, time of year, trust, deprivation, number of previous emergency admissions, number of previous complex admissions, admission source, admission urgency, sex, ethnicity, and Charlson Comorbidity Index:

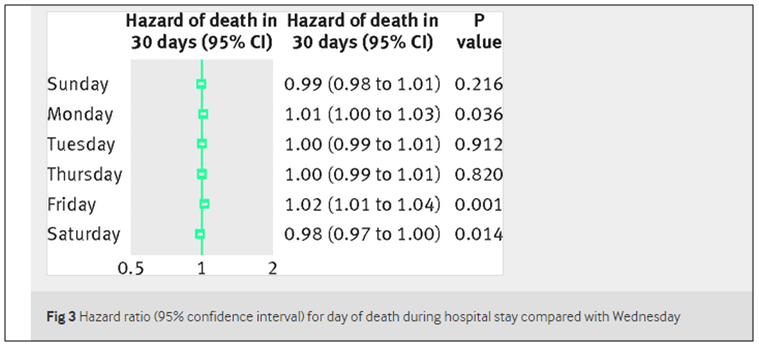

However, patients already in the hospital over the weekend do not have an increased risk of death. One can speculate as to the disparity. An established (and more stable) patient probably incurs less risk of fewer (unrehearsed) staff performing “stuff” on them, in addition to having more limited needs.

The authors sum it up:

Our analysis of 2013-14 data suggests that around 11,000 more people die each year within 30 days of admission to hospital on Friday, Saturday, Sunday, or Monday compared with other days of the week (Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday). It is not possible to ascertain the extent to which these excess deaths may be preventable; to assume that they are avoidable would be rash and misleading. From an epidemiological perspective, however, this statistic is “not otherwise ignorable” as a source of information on risk of death and it raises challenging questions about reduced service provision at weekends.

While some conflict exists in the literature as to the weekend effect–likely stemming from study design, hospital characteristics, or patient service, the contrast seems too stark, and on its face, too valid and consistent to be overlooked.

In addition to ascertaining root causes, some clear, some not (and perhaps it is here where we have the greatest leverage), the remedy in great part will be more dollars to pay for staffing an already overtaxed system cannot spare. What else is new.

Hi Brad,

This seems to be an interesting study with data revealing differences in mortality rates during the course of the week. The reasons I think are open to speculation, and would require further analysis. I think it would be worthwhile to compare with similar data here in the US.

Some of the factors that could influence patient outcomes include staffing changes over weekends and limited availability of specialists. Further analysis to assess if the use of EHR based measures could positively influence the outcomes would be helpful for planning and improving patient care.

Thanks.

Rupesh.

Did they comment on what months during the year pose high risk for death?